“It is required of every man,” the Ghost returned, “that the spirit within him should walk abroad among his fellow-men, and travel far and wide; and if that spirit goes not forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death. It is doomed to wander through the world-ah, woe is me!-and witness what it cannot share, but might have shared on earth, and turned to happiness!”

Again the spectre raised a cry, and shook its chain and wrung its shadowy hands.

“You are fettered,” said Scrooge, trembling. “Tell me why?”

“I wear the chain I forged in life,” replied the Ghost, “I made it link by link, and yard by yard’ I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it. Is its pattern strange to YOU?”

Scrooge trembled more and more.

“Or would you know,” pursued the Ghost, “the weight and length of the chain you bear yourself? It was full as heavy and as long as this, seven Christas Eves ago. You have laboured on it, since. It is a ponderous chain!”

Scrooge glanced about him on the floor, in expectation fo finding himself surrounded by some fifty or sixty fathoms of iron cable, but he could see nothing.

“Jacob,” he said, imploringly, “Old Jacob Marley, tell me more. Speak comfort to me, Jacob.”

“I have none to give,” the Ghost replied. “It comes from other regions, Ebenezer scrooge, and is conveyed by other ministers, to other kinds of men. Nor can I tell you what I would. A very little more is all permitted to me. I cannot rest, I cannot stay, I cannot linger anywhere. My spirit never walked beyond our counting-house—mark me!—in life my spirit never moved beyond the narrow limits of our money-changing hole;; and weary journeys lie before me!”

It was a habit with Scrooge, whenever he became thoughtful, to put his hands in his breeches pockets. Pondering on what the Ghost had said, he did so now, but without lifting up his eyes, or getting off his knees.

“You must have been very slow about it, Jacob, Scrooge observed, in a business-like manner, though with humility and deference.

“Slow!” the Ghost repeated.

“Seven years dead,” used Scrooge. “And traveling all the time?”

“The whole time,” said the Ghost. “No rest, no peace. Incessant torture of remorse.”

“You travel fast?” said Scrooge.

“On the wings of the wind,” replied the Ghost.

“You might have got over a great quantity of ground in seven years,” said Scrooge.

The Ghost, on hearing this, set up another cry, and clanked its chain so hideously in the dead silence of the night, that the Ward would have been justified in indicting it for a nuisance.”

“Oh! Captive-bound and doubled—ironed,” cried the phantom, “not to know, that ages of incessant labour by immortal creatures, for this earth must pass into eternity before the good of which it is susceptible is all developed. But to know that any Christian spirit working kindly in its little sphere, whatever it may be, will find its mortal life too short for its vast means of usefulness. Not to know that no space of regret can make amends for one life’s opportunity missed! And such was I! Oh! Such was I!”

“But you were always a good man of business, Jacon,” faultered Scrooge, who now began to apply this to himself.

:Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

It held up its chain at arm’s length, as if that were the cause of al this unavailing grief, and flung it heavily upon the ground again.

“At this time of the rolling year,” the spectre said, “I suffer most. Why did I walk through crowds of fellow-beings with my eyes turned down, and never raise them to that blessed star which led the Wise Men to a poor abode? Were there no poo houses to which its light would have conducted ME!”

The movies, still in a hurry to get to the GOOD ghosts, cut most of this away. Everyone pretty much likes “I wear the chain I forged in life” and “Business! Mankind was my business!”, though there seems to be an irresistible urge to touch these speeches up to clarify what Dickens SHOULD have meant by them. Otherwise, a brief allusion to the sufferings of this ghost, for the purposes of terrifying Scrooge, is all that is left pf the rest.

Hicks’s Marley gets only as far as “I have none to give” before saying he is here to warn Scrooge, to save him, if possible. “From what?” “From such a fate as mine: to wander through the world.” “But you were always a good man of business.” Marley can then explain, “Mankind should have been my business, as it should be yours.”

Owen watches warily though Marley’s recitation, and grows a bit hangdog by the end. Marley is apparently rendered deadpan by his suffering; he does get to explain how hard he has been travelling these seven years.

Sim I’s Marley now seems to be in thorough agony, and is perhaps a bit mad as well’ all his dialogue comes in face-twisting moans. Sim grovels very low before him, trying to hide behind the collar of his dressing gown now and then; he says Marley has his sympathy. The section about Marley’s travels is omitted.

Marcj’s Marley summarizes the various speeches about his travels at the start, and is told by Scrooge, “You wear a chain. Why?” “I wear the chain I forged in life; a chain of useless things.” Marley recalls some of the villainies he perpetrated, and goes on, “If you died tonight Ebenezer, you would wear such a chain, only longer, stronger.” Marley staggers a bit under the weight of the fetters. “What can I do, Jacob? Speak comfort to me!” Marley replies that he has none to give, and goes on a little more about raveling: why did he always have his eyes on the ground and his mind on the account books? He drags p part of his chain, which includes the account book itself. He opens it to point out the “thousands” of injustices committed by the fir of Scrooge and Marley.

Rathbone listens as Marley reveals that he must wander the earth and witness what he cannot share, but might have shared and turned to happiness. “I wear the chain of selfishness I forged in life.” He explains how he forged it link by link and yard by yard, and makes mention of the length and weight of Scrooge’s own chain. Scrooge asks for words of comfort, and is told these come from other regions.

Magoo’s Marley is brief and, shall we say, businesslike. There is time only for the inquiry about fetters, and the wailing for one captive-bound and double-ironed. They don’t even make time for “You were always a good man of business”. Marley hurries right along to the reason he’s here.

Haddrick’s Marley keeps fading in and out; Scrooge spends time fiddling with his snuffbox. Though they skipped gravy and the grave, they do keep a lot of this section. This Marley must wear chains “as proof of my foolishness”. And he adds “If only you could realize that Christmas spirit is an opportunity to make the chain lighter. I didn’t, and look!” From this we work our way back to “You were always a good man of business” and the rest.

Sim II, like Haddrick, angles the scene so we are watching Scrooge THROUGH the ghost of Marley. His Marley continues to speak without any movement of jaw or lips; being dead, ne needn’t observe such niceties, and, anyhow, his jaw dropped too far open when he removed the chinstrap. He wears the chain he bore in life, and Scrooge tells him he was always a good man of business. He is one of the few Marleys to mention the Blessed Star from the text, though he omits the rest of the line.

Finney demands, “Why do you walk the earth? Why do you come to persecute me? And what is this great chain you wear?” Marley really relishes explaining the chain, adding, “And I can never be rid of it any more than you will ever be rid of yours.” When he notes that comfort comes from other regions, and is conveyed by other messengers to other kinds of men, he raises his hands to block his view of Scrooge. On being told that he was always a good man of business, he replies, “Mankind should be our business, Ebenezer, but we seldom attend to it, as you shall see.”

Matthau’s Marley commands “Look at me! Condemned to walk the earth in death because I wasted my life!” “Wasted? How, dear old Marley?” “I helped myself to money instead of helping my neighbor (sob) and so I wear this chain of greed and heartlessness I forged in life.” There follows a song—“I Wear a Chain”—during which we flash back to scenes of the young Scrooge and Marley gleefully evicting people, collecting money from the poor (presumably widows and orphans), and so forth. He warns Scrooge about the chain, and is told, “But business is business.” Marley cries, “Mankind should have been my business!”

McDuck is treated to a brief version of the “good man of business” section, Marley complaining that in life “I robbed the widows and swindled the poor.” “And all in the same day,” notes an admiring Scrooge, “Oh, you had class, Jacob.” Marleys agrees but then remembers why he’s here. “I was wrong! And so, as punishment, I’m forced to carry these heavy chains through eternity. Maybe even longer! No hope! I’m doomed! Doomed! And the same thing will happen to you, Ebenezer Scrooge!”

Scott’s Marley explains his mission, his lips starting to tremble. A wail of anguish breaks from him. When Scrooge is told about his own chain, he complains that he sees no chains. “Mine,” says Marley, “Were invisible until the day of my death.” We jump from “I have none to give” to “You were always a good man of business.” Scrooge seems not to be applying Marley’s woeful words to himself; he simply says he is sorry for Marley, and asks if there is anything he can do for his old partner.

Caine’s Marley Brothers, Jacob and Robert, break into the song “Narley and Marley”, a number which regrets a life of exploitation compounding the agonies of the poor and homeless. Chains leap up around Scrooge to show him his own peril; the strongboxes sing along. Both ghosts seem exuberant at the outset, but their anguish deepens as the song rolls along.

Curry’s Marley says he is here to warn Scrooge; Scrooge demands to know the meaning of “all this hardware”. Marley explains that he wears the chain he forged in life, and points to individual links, recalling what he did to earn them. A green spark leaps from his finger to each ink he indicates. When told he wears such a chain, Scrooge complains that he sees no such chain. “I can,” intones Marley. Marley then proceeds to the section about it being required of every man that his spirit walk abroad. He mentions the woman and child Scrooge spurned earlier. Scrooge snarls “It’s not my business.” “Mankind is our business,” Marley informs him.

Stewart’s Marley is weary beneath the weight of iron and remorse; it causes pain, apparently, for hi even to talk about it. He describes his WN chain as ponderous, and tells Scrooge that Scrooge’s chain is worse. Scrooge, looking around for a chain and seeing none, seems to reproach Marley for making joes. At one point, Scrooge even breaks into a speech of marley’s with, “Jacob, I don’t understand why you’re suffering. All your life you were a good man of business.” “That’s why I am suffering. The suffering I caused others is being repaid.” Scrooge is adamant: “Jacob, it was business!” Marley points out that mankind is our business, and begins to speak of the common good. Scrooge grins. He’s heard this sort of thing before, and even Marley isn’t going to sell it to him.

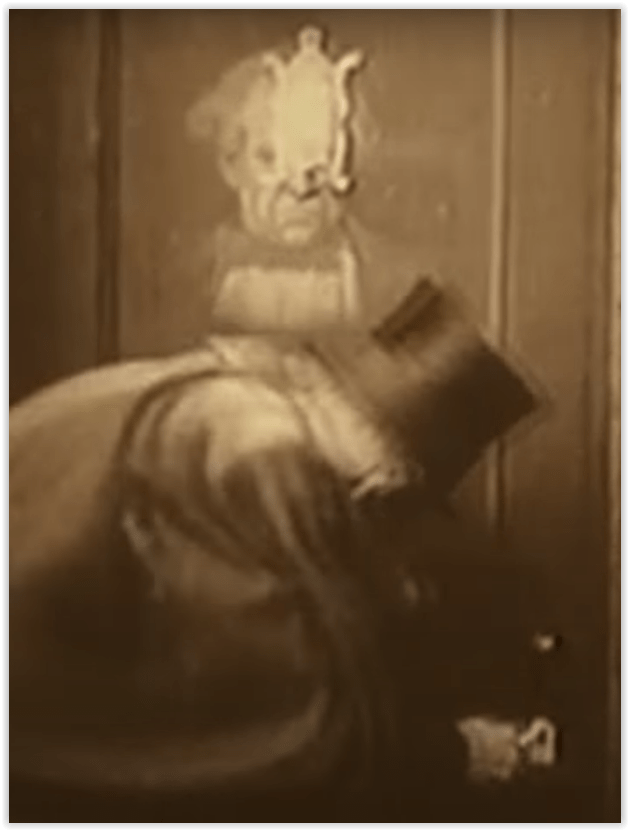

FUSS FUSS FUSS #7: The Late Great Fashion Plate

For once in this story, Dickens is fairly specific about a character’s looks. He can afford to be: this character is going to disappear after this chapter and not come back (until the publication of sequels involving him, but those come from other regions.) Most screen Marleys make at least a token attempt to follow Dickens’s specifications. Whether or not he uses it, Marley almost always wears a chinstrap, and most are well-dressed in the style of a previous generation, with high collars, occasionally alarming neckcloths (see Rathbone’s Marley, who also seems to be wearing his chinstrap almost as a bonnet) and, in the case of Stewart’s Marley, highly polished boots. The spectacles are less consistent, while only Magoo’s Marley, who seems to have left his false teeth at home, has an obvious ponytail. (It’s hard to tell if Finney’s Marley has a pigtail or if that’s a rat disappearing into his hair.) Oddly, only Goofy, as McDuck’s Marley, is clearly wearing the tights mentioned by the author.

The color of Marley’s clothes is hard to determine, since a lot of these ghosts are transparent. Some are dressed all in white, to represent ghostliness as well as to provide a contrast to Scrooge’s darkness. Curry’s Marley, though, is a full-color portrait of a late nineteenth-century robber baron, complete with handlebar mustache. This mustache, like his hair, changes color throughout the show. He is grey in the portrait in Scrooge’s office, but during the scene in Scrooge’s quarters, grey is the one color his hair is not, black or green in the fireplace tiles, red when he pops into full view.

Dickens is not so terribly definite about the chain, which is merely long and heavy and made of office supplies. Screen Marleys have chains which vary in all these particulars, from Haddrick’s Marley, who wears a thin band of itrong links with keys and one strongbox, to Scott’s Marley, who has trouble walking for all this dead ironmongery; the chain is barely visible under all the strongboxes. McDuck’s Marley boasts a modest chain, on which hang one ledger, one strongbox, and one piggy bank, which Scrooge shakes to find out if there’s anything inside. One or two Marleys wear the chain as a belt, but most are wound up in the links, which are fastened behind their backs with padlocks. Sim II’s Marley carries loops and loops of chain.

Most Marleys appear to be at least as old as Scrooge. Matthau and Sim I also show us the young Marley; in both he seems to be a contemporary of his partner. Caine’s Marley Brothers are to be seen later, in the scene of Fozziwig’s Party, where they are called “lads”, though one sports a thick mustache. They seem to be about Scrooge’s age in that scene, but are visibly much older than he when they appear as ghosts. The torments of the damned are probably not conducive to a youthful complexion.