One of the things people do not talk about when studying serious history are the little pleasures and customs of life which have faded away. This is left to people who write mere nostalgia: a loving look back on such disappearing pleasures as the key you had to use to open canned meat or those metal ice cube trays with the recalcitrant lever which might suddenly spread ice all over the kitchen…no, wait. Those are ANNOYANCES of days gone by. Still, that’s the sort of thing I mean.

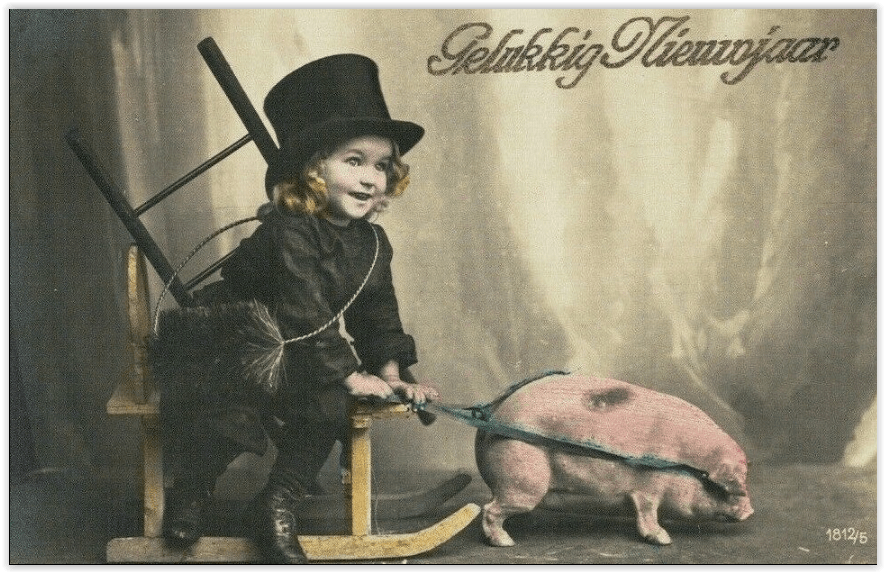

One of the customs I have observed in looking through aged postcards is that there used to be quite a busy custom of sending your friends cards wishing them luck at new Year’s. This has faded away in part because the old style postal service, which could deliver your postcard across town and bring you a reply on the same day, is now gone. Another is that with people spending a billion or so each year on Christmas cards, a New Year’s card seems superfluous, especially to those with hyper-extended bank accounts.

Still, once upon a time, New Year’s was considered a much larger holiday than we consider it. In some parts of the world, Christmas was considered a nice little holiday for the kids, while grown-ups had THEIR big day on new year’s. It was a day for drinking, yes, as we observe it these days,

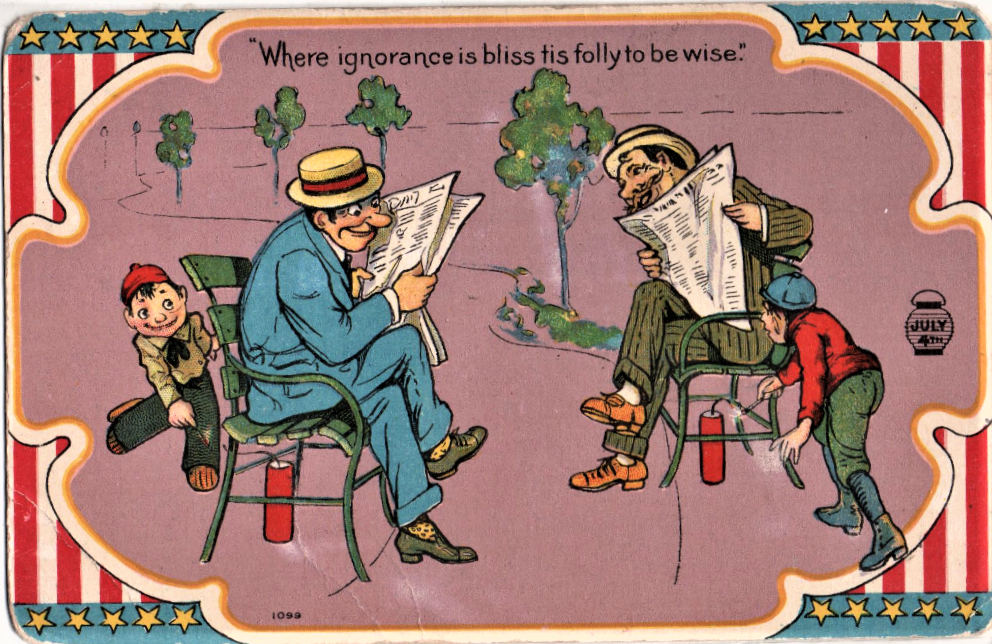

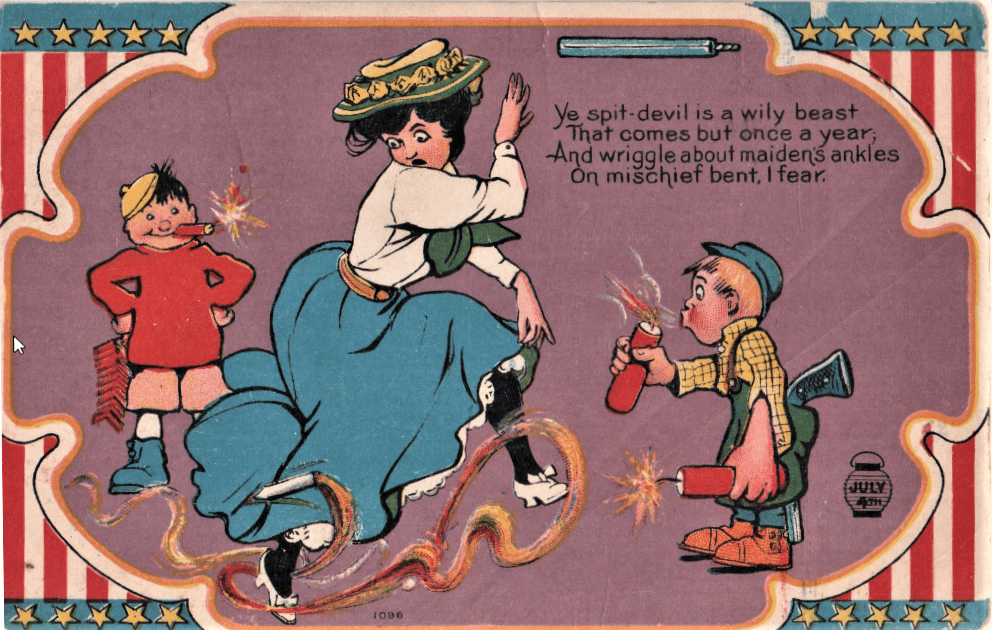

but it was also a day for greeting your customers and creditors, and for dropping in to visit your friends. There was a whole set of rules for what the hair color of the first person to cross your doorstep on new Year’s meant. And above all else, it was a day for wishing each other good luck in the year to come.

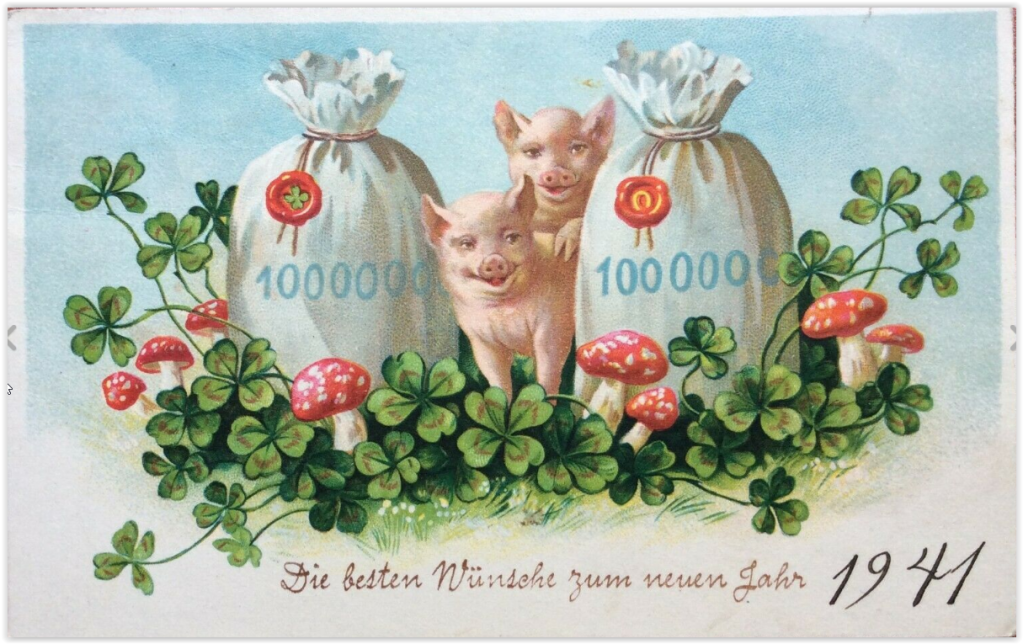

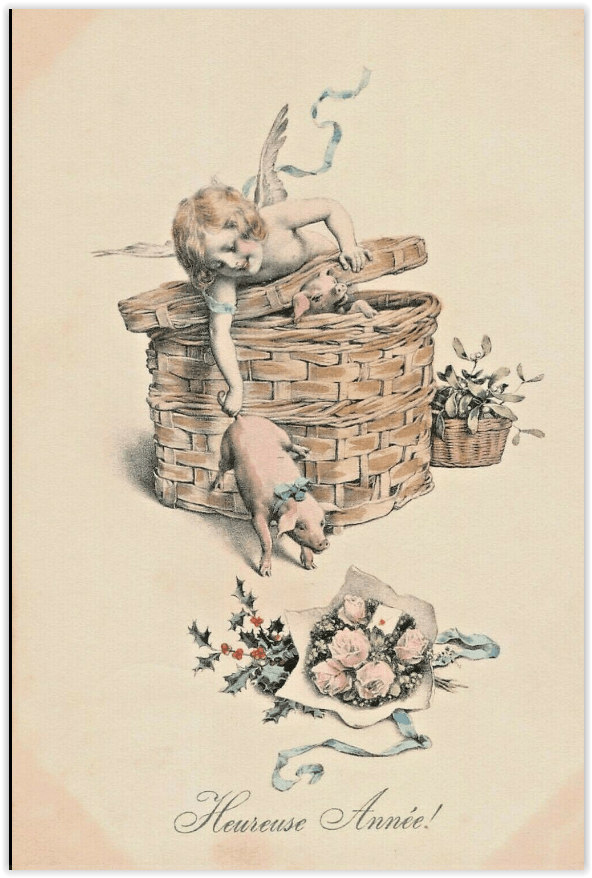

So New Year’s postcards are generally laden with good luck symbols, some of which we recognize today—four-leaf clovers or horseshoes—and some of which make us blink—chimney sweeps (think Mary Poppins) or black cats. And above all else, there were pigs.

To our ancestors, many of whom lived far closer to the land than we even understand now, a pig was a sign of prosperity. A pig was like a savings account: you put things into it and eventually you reaped a profit in bacon, ham, and other useful comestibles.

The pigs on the postcards don’t seem to KNOW this. They are perfectly happy bringing good luck to all, whether they arrive on foot, on a sled, on an airplane, or on a zeppelin. (There are cards where jovial souls are dropping horseshoes and shamrocks AND pigs from airships, without thought of bringing anyone anything but luck.

Luck and/or prosperity are intended by all these postcard greetings. Some of these children, by the way, seem to have made their living posing with pigs, intoxicated or otherwise, and somewhere there were apparently artists who did good business in papier-mache pigs. Millions of these pigs were distributed in the first decades of this century, and in some parts of Europe, the custom continued until postcards themselves started to fade away in the 1970s. A piggy grazing among fly agaric mushrooms and/or piles of gold, was the perfect announcement that 1941 was here, and all would be smooth sailing for the coming year.