In the last column, we dealt primarily with postcard jokes that might be a bit obscure because of changes in our language. Today I thought we might poke out a few jokes which are funnier if you know a little bit about history. All topical jokes run the risk of obsolescence. How will we explain the toilet paper jokes of 2020 to generations who have forgotten to sing to themselves while they wash their hands, and no longer put on latex gloves to fetch the mail? (What, you forgot those already? You see them problem, then.)

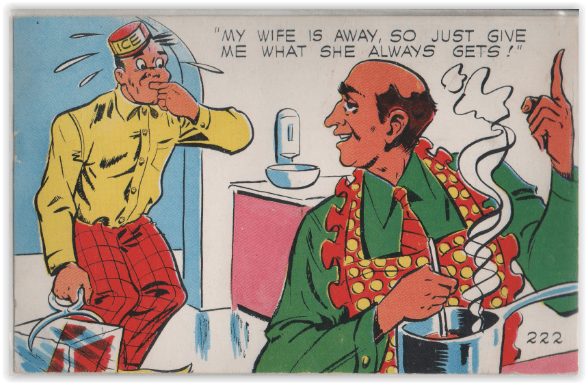

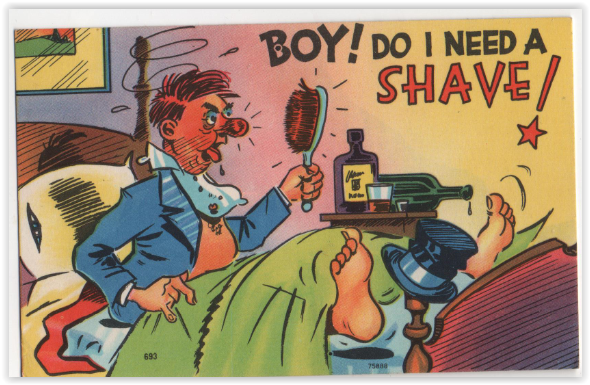

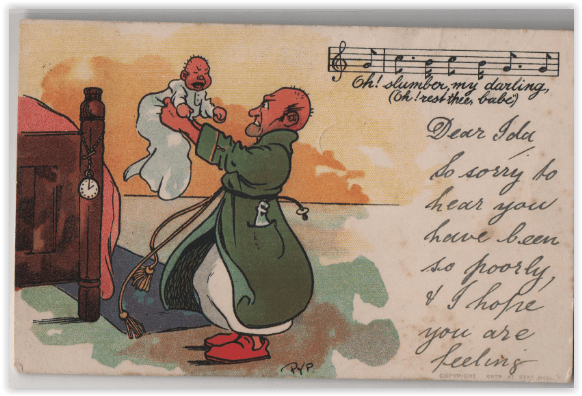

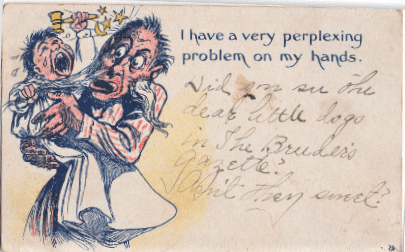

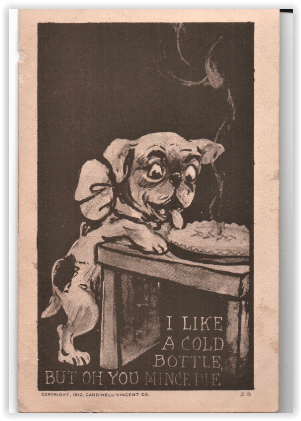

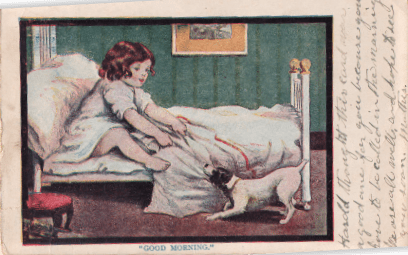

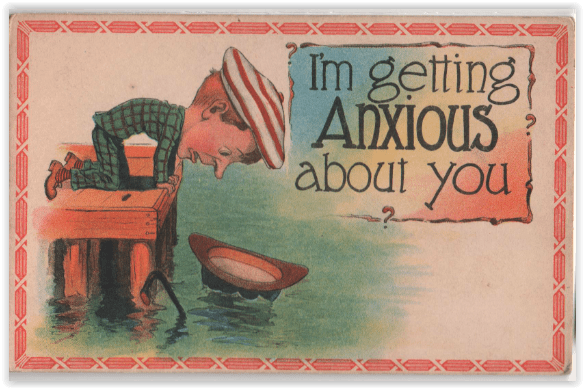

The joke above might be difficult for people who don’t know that once upon a time,, we had no indoor toilets, and to avoid rushing out to the outdoor toilet at night or in winter, we had a chamberpot under the bed or hidden in a small piece of furniture (a cache-pot). This useful utensil rook on an added layer of comedy as more and more people added the modern convenience of an indoor potty: only the backward and/or extremely old-fashioned had such things. There’s such a gag in a classic Looney Tune where our hero puts his head under Grandma’s bed and hits it on something metal. Allowing the audience to chortle, assuming he has hit his head on an old-fashioned and unmentionable fixture, he pulls out Granny’s Air Raid Warden helmet. This is known in parts of the trade as Benny Hill humor, where the audience is given a second to think the punchline is naughty only to be hit with an innocent explanation.

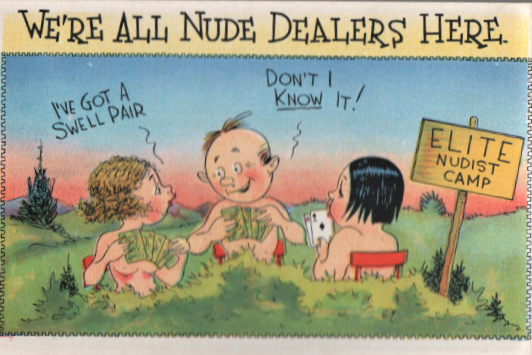

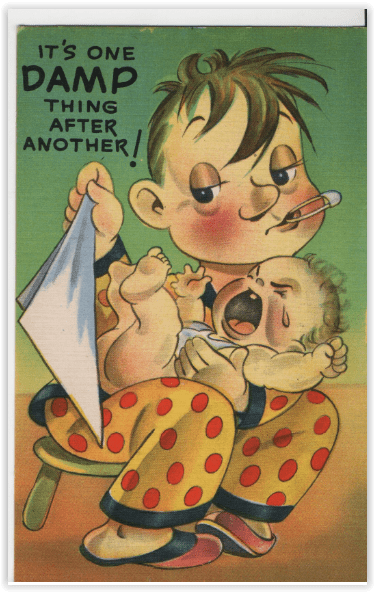

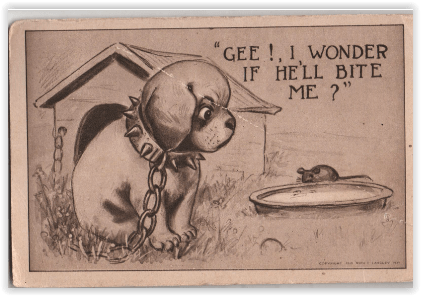

Not so innocent, and understandable only by those people who know what the utensil is FOR, is this card from around World War II.

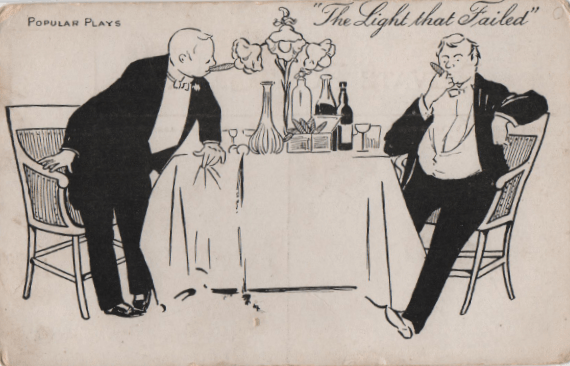

New technology is at the heart of a lot of topical jokes. Here we see a group of club gentlemen utterly stymied. They have tried to light their cigars as they always did, at the gas lamps in the club, only to be foiled by finding the club has gone to electric lights. (AND “the Light That Failed”, used as a punchline on other cards, is a reference to a hit play based on a novel by Rudyard Kipling. TWO bits of history.)

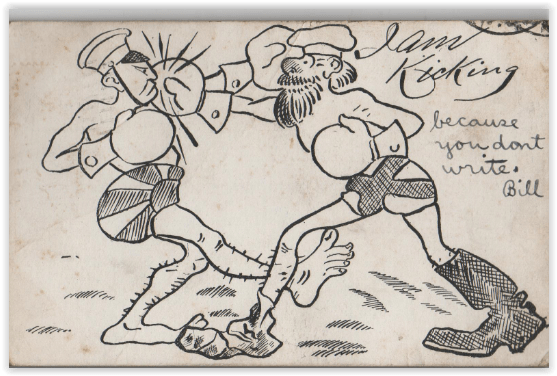

News events, highly important in their day, often are hidden away under new events. This one had me puzzled until I recognized the flag being worn as trunks by the boxer on the left. THEN I caught on to the ethnic stereotypes and got the joke.

This came out at a time when relations between Russia and Japan, never friendly, broke out in the Russo-Japanese War. Theodore Roosevelt won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in negotiating a settlement, but the two countries never did quite get along. (In 1939, when the Japanese government found that Germany had signed a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, the reaction was so fierce that Japan nearly broke off its own pacts with Germany. (Any science fiction writer who wants to consider the various possibilities of alternate history is free to pick this up; use this postcard on your cover and send me royalties.)

It is apparently still possible to send a telegram nowadays, but the proliferation of telephones and, later, the phone in your pocket, removed it from the public eye. Those who are not familiar with the ways of telegrams may be puzzled by dozens of scenes in old movies where someone is reading a telegram aloud. See, telegrams were sent by telegraph through a series of dots and dashes, and a period might have confused things, so when using a period, they called it a “stop” (often shown in telegrams as [stop]) There’s a fine old vaudeville joke…well, if you watch enough old comedies, you’ll see it.

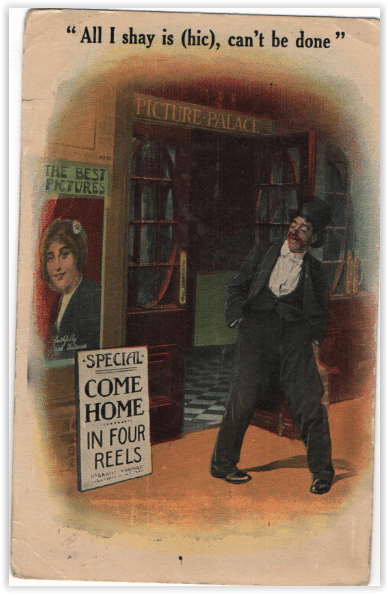

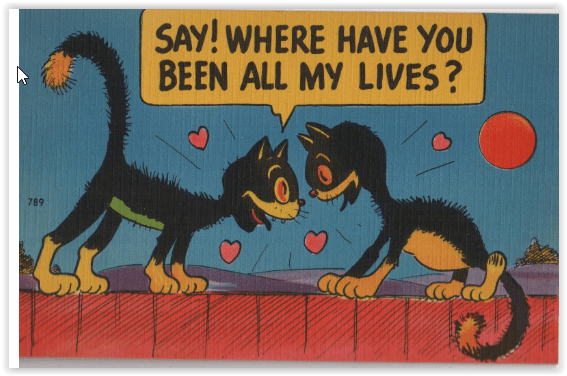

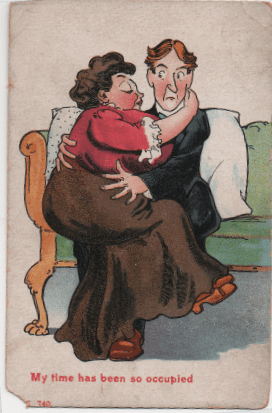

About the same time that joke was new, America was going through a craze of what one critic called “huggly-wuggly dances”. One of the most popular was the Grizzly Bear, which called for the dancers to shout “It’s a Bear!” and then lumber towards each other. This card was able to change to fit the fads. Other versions of it have the hero “enchoying” a Fox Trot, a Turkey Trot, or a Bunny Hug.

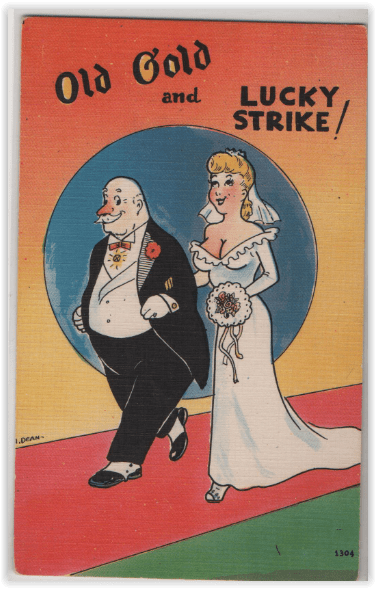

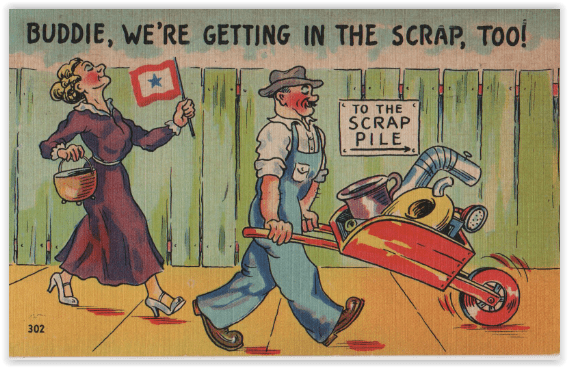

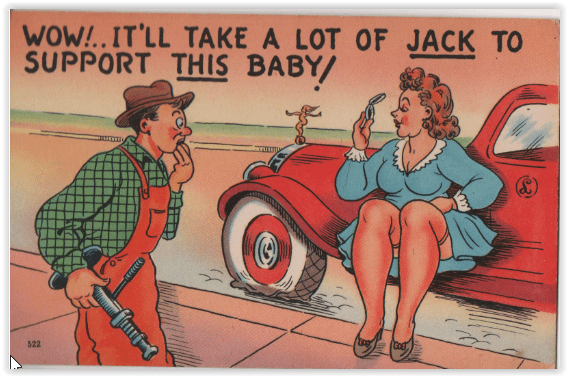

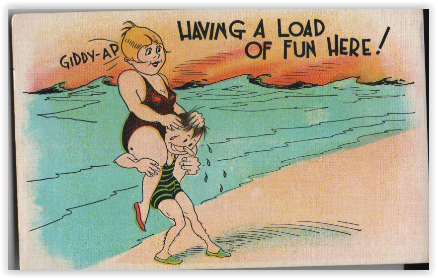

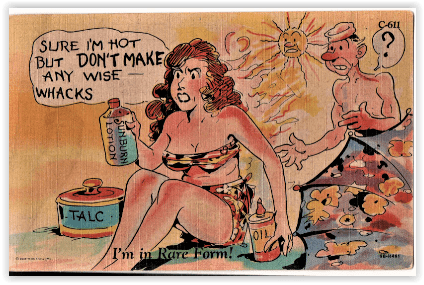

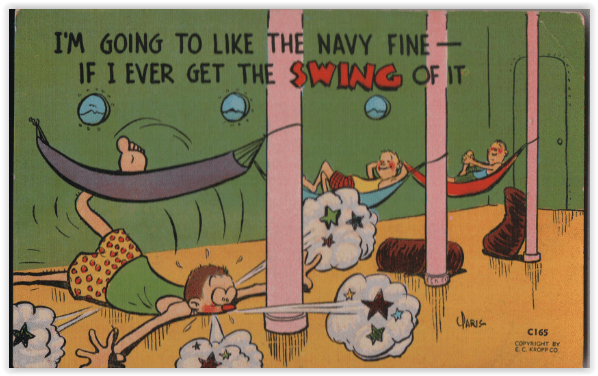

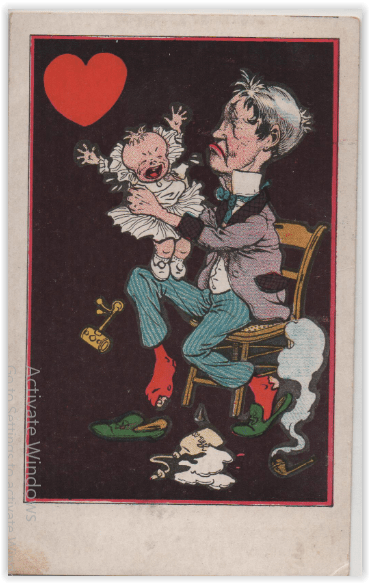

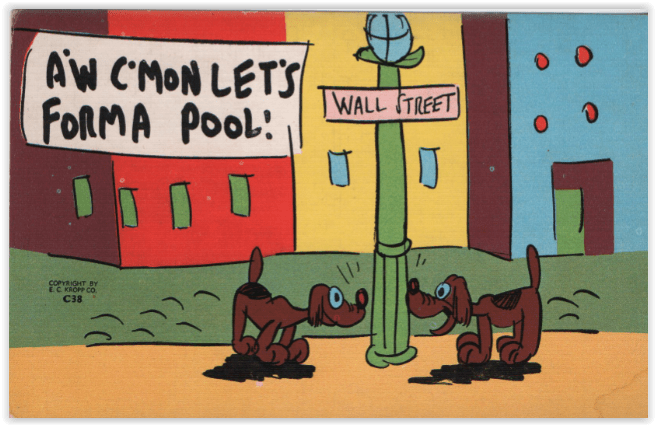

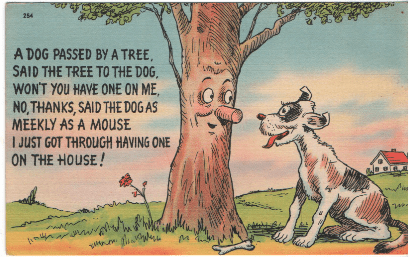

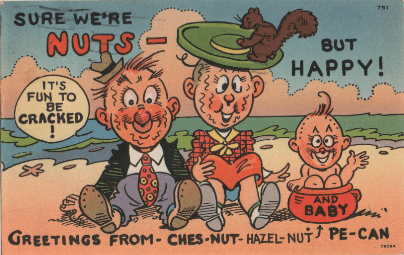

There are plenty of others. Dozens of cards showing people hurrying to Canada or Mexico for beer can be understood only if you are aware of Prohibition, but as long as there are gangster movies, there’s little fear of people forgetting that. There are cards from World War II showing people sleeping with tires chained to their wrists or selling hip flasks of gasoline. But I think we can conclude with a salute to these people who supported Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, even though his Republican opponents warned that all New Dealers would lose their shirts.