This is NOT a column about food. I have sworn that off, This is about ethnic identity, a topic I picked up on when I was informed I was eating Swedes. Learning that it is quite common for rutabagas are also known as Swedish turnips of simply Swedes because they were discovered in Sweden in 1820 (we missed the Bicentennial) I wondered about a lot of these things, and was encouraged to look into this by someone who told me she had always assumed a Belgian waffle was a pancake, and that this was some kind of American insult to the Belgians. So here is a quick quiz: according to the assembled wisdom of the Interwebs, which of the following foreign-named foods were invented in the United States?

Belgian Waffles

French Toast

French Dressing

French Fries

Italian Dressing

Cheese Danish

Russian Dressing

German Chocolate Cake

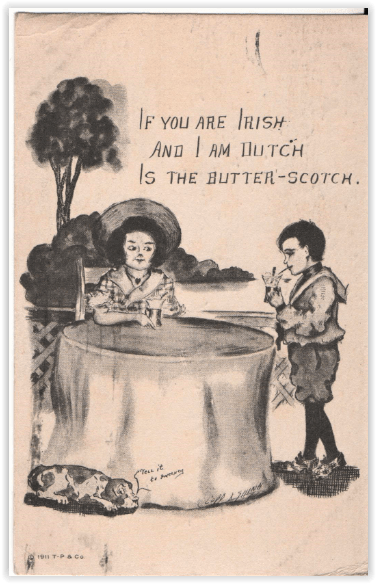

Butterscotch

There is no scoring to be done, simply because I got so many of these wrong myself. Actually only about four of these are our inventions. In some other cases, the country used in the description is actually quite proud of the dish, and refuses to consider the claims of any other country.

Belgian Waffles date to the 1950s, being introduced at a World’s fair in Brussels, Belgium in 1958. The waffles, which are lighter than average waffles, with bigger and deeper squares, were used under strawberries and whipped cream, and in that form, as Brussels Waffles, were served at world’s fairs in Seattle and New York. At the New York World’s Fair in 1964, the seller realized hardly an American knew where Brussels WAS, so he renamed his offering the Belgian Waffle. And that stuck.

French Toast, which my father called “Egged Bread”, has been known by many names since it first appeared in a collection of recipes about 25 centuries ago. The French call it Lost Bread, and Canadians call it Golden Bread. Exactly why it became known as French Toast is debated, on whether this comes from an archaic term meaning to slice, whether a man named French was the first to serve it in a café, or whether calling it French just meant you could charge more for it, since it was fancy.

French Dressing is rejected by a lot of French food commentators. Americans, it seems, lead the world in liking creamy salad dressings with lots of STUFF in them. French Dressing was originally just a vinaigrette, but American chefs and cookbooks started adding ketchup in the 1920s, for reasons lost to history.

French Fries are, on the other hand, hotly claimed by many French experts, who sneer at the rival claims that they were invented in Belgium. Potatoes were an acquired taste in Europe; when the plants were brought from the Americas, Europeans took one look and decided they didn’t like ‘em. The potato’s looks were against it: people decided anything like that must be a cause of leprosy. Famines saw people experimenting with potatoes, and deciding they weren’t so bad after all. At some point, frying strips of them in fat became popular in Belgium and/or France. Thomas Jefferson ate them in Paris, loved them, and always ordered his potatoes “the French way”, when he got back home. So Tom seems to have been the source of the name, at least.

Before we leave the French, we will just note that French Vanilla is called that because it originally used vanilla beans from Tahiti, which belonged to the French at that point.

Italian salad dressing was probably invented at Ken’s Steak House, a restaurant in Massachusetts, in the 1940s. His wife, who was Italian, used to make her family dressing for the house salad dressing, and it became very popular. Other restaurants picked up on the recipe, especially the Wishbone, in Kansas City, Missouri, which got so many demands for it that it had to start a separate shop just to make salad dressing (which it still does today.)

Danish pastry was invented in Denmark. Says Denmark. Austria and France have put in their claims, too. The story goes back to a baker’s apprentice in France who forgot to blend butter into his pastry dough until it was otherwise completely finished. So he layered the butter between folds of the dough, figuring no one would notice. They noticed, and they loved it. His recipe spread from there to Austria. Austria was the source of a number of bakers hired in Denmark in 1852 when Danish bakers went on strike. They brought this recipe with them, and when the strike ended, Danish bakers took it over and altered the amount of eggs and butter to make it uniquely theirs (the French and Austrians sniff at this.) This is why Danish pastry is known as Vienna Bread in most of Denmark. (Cheese fillings were popular throughout Europe, so that wasn’t our idea either.)

Russian dressing seems to have been invented in New Hampshire by a man who was already selling mayonnaise. He toyed with the recipe, added ingredients, and came up with what he called Russian salad dressing. I was not clear on whether his recipe included caviar, but a number of them did, enhancing the Russian identity.

In 1852, an American company, Baker’s Chocolate, introduced a new dark chocolate for baking, called Baker’s German’s Baking Chocolate. They called it that because it had been developed for them by a baker named Samuel German. In 1957, a woman sent a recipe called German’s Chocolate Cake to a newspaper in Dallas, and it was a huge hit. Baker’s Chocolate saw it, distributed it as widely as possible, and saw sales of German’s Chocolate skyrocket. (No one is quite sure when the apostrophe and s were dropped.)

Butterscotch, which some people adore and others regard as a low-class poor cousin of caramel, seems to have been produced in England in the seventeenth century. No one is sure how the Scots got mixed into it, though some people believe Scotch was a necessary ingredient (no evidence for this) while others derive it from an archaic word meaning slice (see French Toast, above; this is getting silly.) Some feel the original recipe came about when someone scorched his caramel. We need to scotch these rumors.

So we are basically responsible only for three salad dressings, and one cake recipe, most of which date from mid-century (the Russian dressing recipe dates to before World War I.) Run out and celebrate this with some Belgian waffles with butterscotch syrup. (You can out French dressing on them if you want to: just don’t tell me about it. Have some rutabagas on the side.)