We strayed a little from the path in this column and discussed food again on Wednesday, but we are going to get right back to business today. We will waste no more time on tales like that of the French kitchen assistant who invented Danish pastry.

Oh, come now: you saw that on Wednesday. A chef’s apprentice named Claudius Gelee forgot to put any butter in his pastry dough until it was ready to bake, and decided if he slipped butter between the layers, that would do just as well. It wound up doing better, and the rest is at least supposed history.

Yes, we do have our own American variant on the story, about Ruth Wakefield, cooking at the Toll House restaurant (remember the name; it comes back into the story.) She was making some chocolate cookies, ‘tis said, and found out she didn’t have any baking chocolate the recipe called for. So she busted up a bar of Nestle’s semi-sweet chocolate and put that in instead, figuring it would melt. The resulting cookies with lumps of chocolate in them were a hit, and during World War II, when these cookies were sent to soldiers who had eaten them at the Toll House, the recipe caught on. Nestle bought the recipe and the chocolate chip cookie went around the world. It’s one of the great tributes to American ingenuity, and part of our natural culture.

One problem is that Ruth Wakefield generally denied the story. Yes, it weas a nice story, but she always claimed she came up with the recipe on purpose, because she wanted something a little different than the butterscotch nut cookies she always served with ice cream, and knew very well the chunks of chocolate wouldn’t melt and make plain chocolate cookies. Anyway, she and Nestle lived happily ever after, whichever story is true. (Nestle bought the recipe from her for a lifetime supply of chocolate. Makes me want to get out there and invent.)

My mother never got paid for the recipe, but she had a dessert she came up with in the same desperate tradition. According to her story, she was getting things ready for her father to have lunch when he walked home from the sash and door company. She realized, in a panic, that there was nothing in the house that would do for a working man’s dessert. (My grandfather spent most of his life as middle management, which meant he spent half of every day walking the factory floor to inquire how certain orders were coming along, and trying to make sure things went the way which would gladden the heart of the customer. He called himself an “expeditor”.)

She couldn’t run out to the store and buy anything (no allowance for teenagers in those days: “You’d just spend it.”) She had to improvise with what was in the kitchen. She made a pie crust, feeling that was at least a start in the right direction. Grabbing a box of vanilla pudding, she started that on the stove. But you could NOT just pour vanilla pudding in a crust and call it a pie (you could with chocolate, but such are the vagaries of our culture.) She grabbed a can of peaches, drained the liquid, poured the peaches in the pie shell, poured the vanilla pudding over that, and put the concoction in the icebox to cool. I do not know if she had recourse to whipped cream for the topping, but the result was approved, and became one of her stalwart recipes. I have not seen this elsewhere, though I suppose there must be other cooks who have known the same sort of desperation. Imagine my surprise when I grew up and found that other people’s “Peach Pie” was something quite different.

It reminds me of a friend of mine, a genius, who had to feed her son, who had quietly expiring from starvation, having had nothing to eat since lunchtime but a few raisins, some Gummibears, and half a cookie she hadn’t been quick enough to finish herself. She had been to the store and bought hot dogs, but realized, in horror, while they were cooking that she was entirely out of bread. All she had were a few soft corn tortillas she used in making quesadillas.. So with a prayer that her son, who sounds as if he was a judgmental a diner as my grandfather, would accept it, she put a piece of cheese on a tortilla and rolled this around a hot dog.

The lad looked this over and explained “Aha! A dogadilla!” And another family recipe was born.

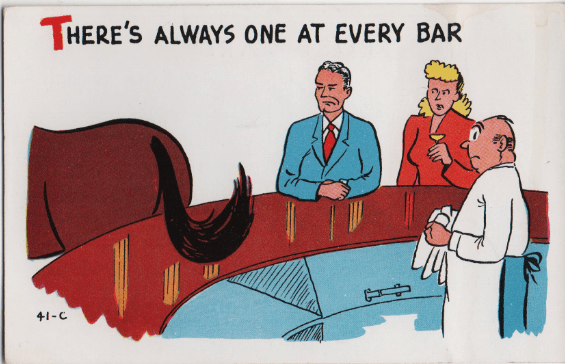

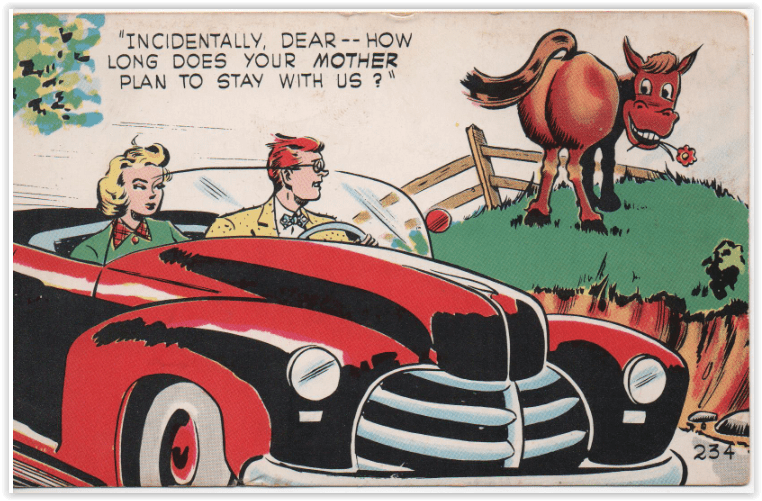

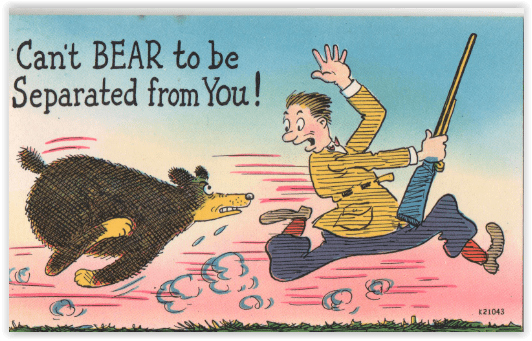

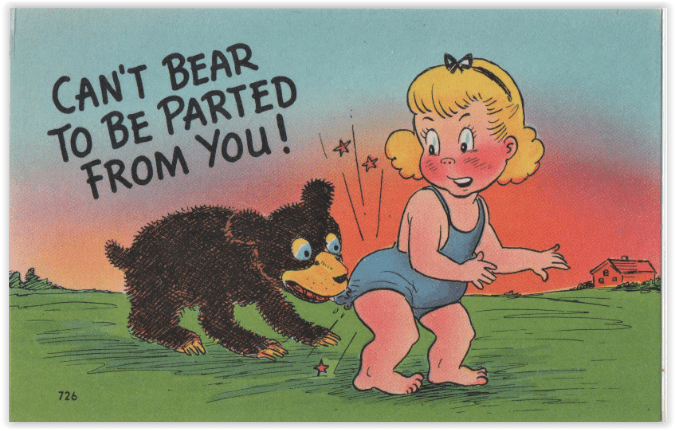

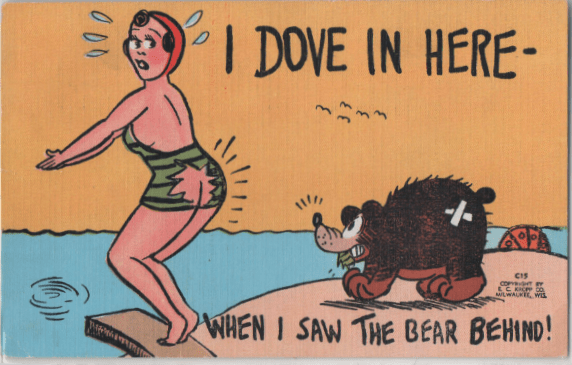

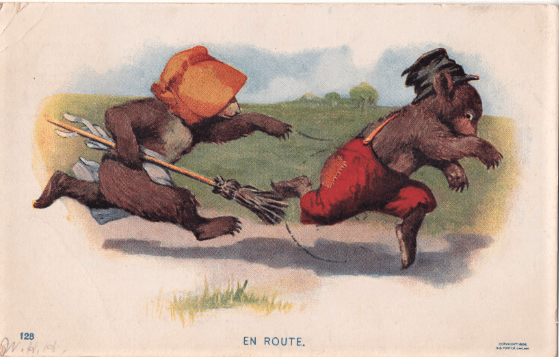

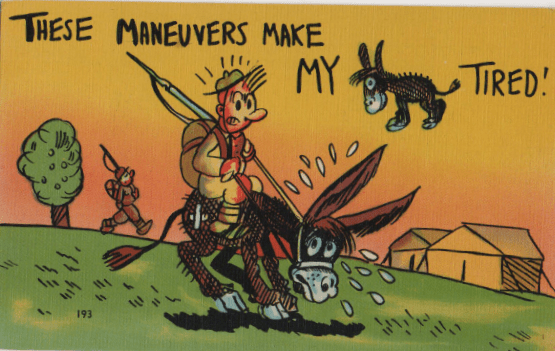

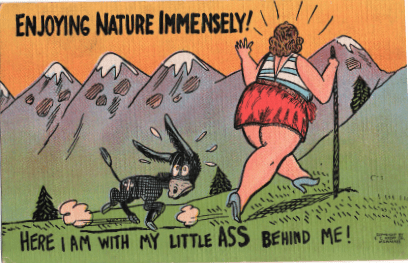

But anyway, the postcards I wanted to discuss today….