Scrooge bent before the Ghost’s rebuke, and trembling cast his eyes upon the ground. But he raised them speedily, on hearing his own name.

“Mr. Scrooge!” said Bob; “I’ll give you Mr. Scrooge, the Founder of the Feast!”

“The Founder of the Feast indeed!” cried Mrs. Cratchit, reddening, “I wish I had him here. I’d give him a piece of my mind to feast upon, and I hope he’d have a good appetite for it.”

“My dear,” said Bob, “the children; Christmas Day.”

“It should be Christmas Day, I am sure,” said she “on which one drinks the health of such an odious, stingy, hard, unfeeling man as Mr. Scrooge. You know he is, Robert! Nobody knows it better than you do, poor fellow!”

“My dear,” was Bob’s mild answer, “Christmas Day.”

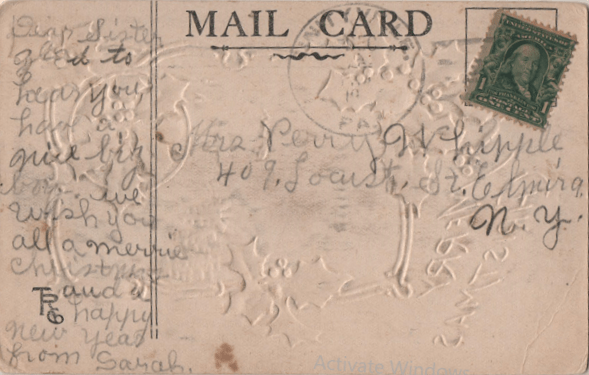

“I’ll drink his health for your sake and the Day’s,” said Mrs. Cratchit, “not for his. Long life to him! A merry Christmas and a happy new year!—he’ll be very merry and very happy, I have no doubt!”

The children drank the toast after her. It was the first of their proceedings which had no heartiness in it. Tiny Tim drank it last of all, but he didn’t care twopence for it. Scrooge was the Ogre of the family. The mention of his name cast a dark shadow on the party, which was not dispelled for full five minutes.

After it had passed away, they were ten times merrier than before, from the mere relief of Scrooge the Baleful being done with. Bob Cratchit told them how he had a situation in his eye for master Peter, which would bring in, if obtained, full five-and-sixpence weekly. The two young Cratchits laughed tremendously at the idea of Peter’s being a man of business; and Peter himself looked thoughtfully at the fire from between his collars, as if he were deliberating what particular investments he should favour when he came into the receipt of that bewildering income. Martha, who was a poor apprentice at a milliner’s, then told them what kind of work she had to do, and how many hours she worked at a stretch, and how she meant to lie a-bed tomorrow morning for a good long rest; tomorrow being a holiday she passed at home. Also how she had seen a countess and a lord some days before, and how the lord was “much as tall as Peter”; at which Peter pulled his collars so high that you couldn’t have seen his head had you been there. All this time the chestnuts and the jug went round and round; and bye and bye they had a song, about a lost child travelling in the snow, from Tiny Tim; who had a plaintive little voice, and sang it very well indeed.

There was nothing of high mark in this. They were not a handsome family; they were not well-dressed; their shoes were far from being water-proof; their clothes were scanty; and Peter might have known, and very likely did, the inside of a pawnbroker’s. But they were happy, grateful, pleased with one another, and contented with the time; and when they faded, and looked happier yet in the bright sprinklings of the Spirit’s torch at parting, Scrooge had his eye upon them, and especially on Tiny Tim, until the last.

The screenwriters often move this scene around, or combine it with the “God bless us” toast, but few omit it entirely. There’s too much going on. Mrs. Cratchit gets her big speech (and Dickens indulges a practice for making women the voice of reason in this story) Our opinion of Bob Cratchit as one of those “No, everything’s all right, really” sort is confirmed. And we get to twist the knife just a wee bit more in Ebenezer Scrooge.

Hicks has the dialogue much as written. The toast is drunk with no great willingness. Tiny Tim, at request, sings “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing”, since the experts have never quite figured out what song Dickens had in mind when he wrote the passage. (Still, there are so many songs about children lost in the snow/forest/jungle/big city/darkness/high weeds that it might be a version of any of those.)

Owen accomplishes a major shift by having Mrs. Cratchit propose the toast to Mr. Scrooge. “And here’s to next Christmas, may it bring us luck. And may Mr. Scrooge give your father a raise!” Martha and Bob, the only ones who know Bob has been sacked, look somber. “And a merry Christmas to Mr. Scrooge!” Nob says, “I can drink to that.” Scrooge is much abashed by all this. “And now a story!” Bob prepares to tell the children a story; Scrooge is eager to hear it. “It’s about Aladdin!” he tells the Ghost, “And the magic lamp!” After some coaxing, the Ghost is able to tear him away.

In Sim I, Peter brings in the gin punch, and has some actual lines. We hear the bit about Peter’s possible job. The “God bless us” toast make Scrooge look rueful; his face really drops when the next toast is proposed, even before the family starts to boo and shout objections. Thoroughly miserable, he turns to go, but the Ghost stops him. The speeches are delivered more or less as written, and the lack of enthusiasm when the toast is finally drunk is obvious. The scene fades in smoke.

March omits this toast.

Magoo pushes this scene to the very end, just before Scrooge appears, in the flesh, at the Cratchit household. Some of the dialogue is omitted, but the toast is drunk with a thorough lack of enthusiasm. Bob reproves the children, asking them to do justice to the day and to this marvelous turkey they are about to eat (having no idea that the reviled Founder of the Feast sent it.)

Haddrick keeps the dialogue as written through “My dear! Christmas Day!” when Bob adds “I’m sure Mr. Scrooge is a good man under hs hard front. After all, he is a businessman.” “And his business is making people unhappy,” comes the reply. Then Mrs. Cratchit delivers her line about Scrooge being very merry and very happy, she’s sure. “Are you very merry and happy?” the Ghost asks Mr. Scrooge. “After that, I have cause to be. But I’m not.” “Why is that so?” Scrooge explains he is unhappy for worrying about Tiny Tim; he now inquires about the boy’s future, as explained in the last chapter.

Sim II omits the scene.

In Finney, Bob toasts Tiny Tim for the fortune he’s made caroling, and joins this to a toast to Mr. Scrooge, naming them as the two individuals whose industry and generosity have provided the feast. Mrs. Cratchit and the others thump their cups on the table, refusing to drink the toast. “What are you trying to do?” Mrs. Cratchit demands, “Ruin our Christmas?” “But his money paid for the goose, my dear.” “No, YOUR money paid for the goose, my dear.” “But he paid me the money.” :because you earned it.” She points out that Bob hasn’t had any raise in eight years. “My dear, Mr. Scrooge assures me times are hard.” “For you they are, not for himself.” Bob, digging in his heels, insists, “Nonetheless, he is the founder of our feast and we SHALL drink to him.” Mrs. Cratchit is not intimidated. “The Founder of the Feast indeed!” We return to our regularly scheduled dialogue through “My dear! Christmas Day!”, with a modest embellishment in her opinion that a piece of her mind would give Mr. Scrooge indigestion for a month. She finally turns to the others and announces, “Children, we shall drink to your father and Tiny Tim. And for the sake of your father, I’ll even drink to that old miser Mr. Scrooe. Long life to him and to us all.” “A merry Christmas to us all.” Now we can move to the God bless us every one toast, and the song “The Beautiful Day” from Tiny Tim.

Matthau omits the scene. It exists in McDuck only as the mournful look on Mrs. Cratchit’s face when Tiny Tim suggests thanking Mr. Scrooge for all the wunnerful food.

Scott seems impatient to leave; when the pudding has arrived and been approved by the head of the household, he is glad to be finished. The Ghost detains him. “Just one more ceremonious moment. Look!” Bob kisses his wife under the mistletoe, and then proposes a toast to Mr. Scrooge, the Founder of the Feast. The children rise slowly to drink it, and Mrs. Cratchit sits down hard, to deliver the “Founder of the Feast indeed!” speech. “My dear, have some charity.” She thinks this over. “Very well, I’ll drink his health for your sake and the Day’s” and so forth. Everyone drinks as if they are imbibing some vile medicine. Scrooge points out that Bob made a good point: without him, there would have been no Christmas feast. “My head for business furnished him employment.” “Is that all you’ve learned by watching this family on Christmas Day?” “No. Not all. But one must speak up for oneself, for one’s life.” The family have a better time with the toast out of the way, and start singing “The Wassail Song”. “We have some time left,” says the Ghost, “Tale my robe.” They look toward the window, and a bright light.

Caine hears Bob say “Mr. Scrooge,” and walks through the wall to answer. Bob is proposing thr toast; his wife objects, going on to say “I would give him a piece of my mind to feast upon, and I bet he would choke on it.” “:Choke!” agree Bettina and Belinda. “My der. The children. Christmas Day.” Mrs. Cratchit is a bit flustered at having vented unpleasant opinions on Christmas Day. “Oh. Well, I suppose that on the blessed day of Christmas, one must drink to the health of Mr. Scroooooooge, even though he is odious.” Belinda and Bettina nod. “Stingy.” Bettina and Belinda nod. “Wicked.” Bettina and Belinda nod. “And unfeeling.” Bettina and Belinda nod. Scrooge looks up anxiously at the Ghost. Mrs. Cratchit goes on, “And badly dressed.” Bettina and Belinda gasp in horror at how far their mother is going. “And….” Tim breaks in with “To the Founder of the Feast! Mr. Scrooge!” His mother relents. “To Mr. Scrooge! He’ll be very merry and very happy, I have no doubt.” “No doubt!” snap the twins. “Mmmm,” says their father, not perfectly convinced of the sincerity of the toast. “Cheers.” Now Tiny Tim sings “Bless Us All”; the family chime in. Tim ends with a coughing fit, badly frightening Scrooge. The Ghost draws him away, and Dickens reads us the closing line of the text.

Curry has the toast to Mr. Cratchit, and then a toast to Mr. Scrooge, which becomes an excuse to reprise the song “Random Acts of Kindness”, this time phrasing it to explain how much happier we are with each other than Scrooge is with all his money. Scrooge grumb;es, “I provide them with an income, and this is how they treat me.”

Stewart begins with Bob proposing the toast; Mrs. Cratchit is stunned. “Did you say Scrooge, Founder of the Feast?” “Well, my dear….” The written dialogue appears now, starting with “Founder of the Feast indeed!”; Bob recoils under the impact of “odious, stingy” and the other adjectives. When convinced to go ahead with the toast, Mrs. Cratchit rushes through the words to get them out of her mouth all the faster. “A nice gesture,” the Ghost remarks, But Mrs. Cratchit hasn’t finished. “He’ll be about as merry as a graveyard on a wet Sunday.” The Ghost laughs; Scrooge is offended. Tim sings “Silent Night”; his brother looks grave. The Ghost draws Scrooge outdoors.