“Spirit,” said Scrooge, “Something informs me that our moment of parting is at hand. I know it, but I know not how. Tell me what man that was we saw lying dead?”

The Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come conveyed him, as before—though at a different time, he thought; indeed, there seemed no order in these latter visions, save that they were in the future—into the resorts of business men, but showed him not himself. Indeed, the Spirit did not stay for anything, but went straight on, as to the end just now desired, until besought by Scrooge to tarry for a moment.

“This court,” said Scrooge, “through which we hurry now, is where my place of occupation is, and has been for a length of time. I see the house. Let me behold what I shall be, in days to come.”

The Spirit stopped; the hand was pointed elsewhere.

“The house is yonder,” Scrooge exclaimed. “Why do you point away?”

The inexorable finger underwent no change.

Scrooge hastened to the window h=of his office, and looked in. It was an office still, but not his. The furniture was not the same, and the figure in the chair was not himself. The Phantom pointed as before.

He joined it once again, and wondering why and whither he had gone, accompanied it until they reached an iron gate. He paused to look round before entering.

A churchyard. Here, then, the wretched man whose name he had yet to learn, lay underneath the ground. It was a worthy place. Walled in by houses; overrun by grass and weeds, the growth of vegetation’s death, not life; choked up with too much burying, fat with repleted appetite. A worthy place!

The Spirit stood among the graves, and pointed down to One. He advanced towards it trembling. The Phantom was exactly as it had been, but he dreaded that he saw new meaning in its solemn shape.

“Before I draw nearer to that stone to which you point,” said Scrooge, “answer me one question. Are these the shadows of the things that will be, or are they the shadow of things that may be, only.”

Still the Ghost pointed downward to the grave by which it stood.

“Men’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they will lead, said Scrooge. “But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change. Say it is thus with what you show me!”

The Spirit was as immovable as ever.

Scrooge crept towards it, trembling as he went; and following the finger, read upon the stone of the neglected grave his own name. EBENEZER SCROOGE.

“Am I the man who lay upon the bed?” he cried, upon his knees.

The finger pointed from the grave to him, and back again.

“No, Spirit! Oh, no, no!”

The finger still was there.

“Spirit!” he cried, tight clutching at its robe, “Hear me! I am not the man I was. I will not be the man I must have been but for this intercourse. Why show me this, if I am past all hope?”

For the first time the hand appeared to shake.

“Good Spirit,” he pursued, as down upon the ground he fell before it. “Your nature intercedes for me and pities me. Assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me, by an altered life!”

The kind hand trembled.

“I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the past, Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach. Oh, tell me that I may sponge away the writing on this stone!”

In his agony, he caught the spectral hand. It sought to free itself, but he was strong in his entreaty, and detained it. The Spirit, stronger yet, repulsed him.

Holding up his hands in a last prayer to have his fate reversed, he saw an alteration in the Phantom’s heed and dress. It shook, collapsed, and dwindled down into a bedpost.

Scrooge, realizing how much the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come resembles the Grim Reaper, is struck with a new idea. Marley lied to him! This is not a chance at reclamation, but the beginning of his eternal punishment just a way of introducing him to the same fate as his old partner, to wander the earth and witness scenes he cannot take part in. Scrooge begs for mercy NOT because he is horrified by death, but by the possibility that all the horrors he witnessed in the future will come to pass without his ever getting a chance to fix anything.

Nobody, nobody, nobody leaves this out. The shock of wandering through an ugly graveyard and stumbling upon your own tombstone can’t be wasted. (Though no one much uses the bit about Scrooge running to look in at the place he worked so many years and finding it is now occupied by someone else.)

Hicks asks, “Now, Spirit, tell me…what man was that whom we saw lying dead?” He seems to suspect what the answer is. We are suddenly among gravestones in the snow; it is dark. Scrooge is shaking on his knees, his voice breaking as a particular stone is indicated. His tone is desperate as he asks if these are the shadows of things that may be, only. The finger points, and just after we see the name, there is a wail of “Ebenezer Scrooge!” He drops to all fours. “Am I the man who lay upon the bed?” The finger moves from him to the grave. “No, Spirit, no!” The finger insists. Scrooge cries that he is not the man he was, and so forth. Catching at the hand, he is repulsed. He drops, scratching at the writing on the stone, only to find he is mauling a pillow.

“Spirit.” Owen’s jaw juts; his will is hardened by suspicion. “Tell me the name of the man we saw lying dead.” He is fierce. “Tell me!” A gate opens, allowing us to enter a crowded necropolis, where mausolea, tombstones, and other statuary crowd each other. He asks whether these are the shadows of things that may be, only, and receiving no answer, goes on “Men’s lives lead to certain ends” and so forth. Still getting no response, he turns to look and sees the stone. He buries his face in his hands. “Then I was the man who lay upon the bed.” The finger moves from him to the grave. “No no. Why show me this if I am past all hope? I shall change my way of living. I will try to keep Christmas all the year” and the rest of that plea. “Tell me that this will change my future. Tell me that this is not my end! Please!” He clutches at the Spirit’s sleeve, but the Spirit pulls back out of reach. When he reaches for it again, he finds he is reaching to his own bedcurtain.

Sim I is looking around for himself in the Exchange and finds it transformed into a spacious graveyard clogged with grotesque trees. Clutching a tombstone, he asks if these are the Things That Must Be or Things That Might Be Only. He hears singing, and covers his ears in despair. “I know that men’s deeds foreshadow certain ends,” he says, and so on. The Ghost insists and Scrooge staggers forward to find a large stone flat upon the ground; he falls, weeping, across the name we see on it. “No, Spirit! No no no no! Tell me I’m not already dead!” Repeating himself quite a lot, he says he is not the man he was, why show him this if he is past all hope, and ends with “Pity me! Pity me and help me! Help me sponge away the writing on this stone.” He goes on and on with more of “I’m not the man I was”. When he looks up again, he is kneeling before his bedpost, clutching the base.

March is still standing before the display of plate and china and books in the Cratchit sideboard when he spots the raven that few from his own table, now sitting in a tree outside the window. The camera lowers to show this tree stands in a fog-infested, ramshackle graveyard. Scrooge is now wandering within this; the raven startles him, and Scrooge backs from the tree to a stone we read before he does. Seeing it, he shrieks, raising his eyes. Dropping to his knees in despair, he looks up to see a smaller stone marked ‘TINY TIM”. He strikes at this crying “No no no”; soon he is punching the head of his own bed.

The Spirit guides Rathbone into a graveyard that is as knee-deep in fog as any other scene Scrooge has visited. He asks why they are here, and goes on to inquire about the things that Will Be and the Things That My Be, Only. The Spirit points. Scrooge kneels to read a horizontal stone and cries “No no no no!” Looking up, he implores, “I am not the man I used to be! I will change! Why show me this if I am past all hope? I will honor Christmas and try to keep it all the year. Tell me—oh, tell me!—that I may sponge away the writing on this stone!” He falls across the marker and vanishes. The fog closes in to hide the stone as well.

Magoo demands, “Spirit! Show me my future self!” Red gates open and they move into a lonely cemetery, with more trees than stones. Scrooge, terrified, lifts the Spirit’s skirts in front of his face. The Spirit points to a stone we cannot read. “What…what is this?” Scrooge bites his lower lip and asks whether these are the shadows of the Tings That Will Be or the Things That Might Be. The Spirit points. Scrooge crawls forward to read the writing on the stone: some lightning makes it easier. “No no!” he cries, scuttling back the way he came. “I will honor Christmas in my heart,” he pleads, “And try to keep it all the year. And I will not shut out the lessons that have been taught to me. I promise! Tell me that I may sponge away the writing on this stone!” The Spirit’s hand shakes a bit, but continues to point. “I beg of you: give me some sign that I may be saved from this!” The Spirit dissipates, leaving Scrooge to weep at his own grave. He reprises the song “All Alone In the World”. Later, he will wake up in bed.

Haddrick orders, “Return me to my own time.” He pauses. “But before you do…tell me what man that was whom we saw lying dead.” They move into a dark and cluttered cemetery. We spot the name on the stone, but he does not; he is wondering whether these are the shadows of the Thing That Will Be, or That Might Be. Seeing the name on the stone, he asks, in honest surprise, “Am I the man who lay upon the bed?” going on, weakly, “Who was robbed? And scorned?” The finger points. “No, Spirit! No! No!” The finger continues to point. “Spirit, hear e! I am not the man I was! I will not be the man I have been! You and your companions have shown me my errors. I shall change. I will honour Christmas in my heart and try to keep it all the year. Why show me this, if I am beyond all hope?” The Spirit stands with arms folded. “I shall not shut out the lessons you have taught. And I shall sponge the writing from this tone. Oh, tell me that I may!” The Spirit raises its hands, calling forth lightning. Scrooge finds himself on all fours in his bed.

Sim Ii is transported quickly into the center of a bristling grove of tombstones, sticking up low rows of crooked teeth. Scrooges asks if these are the shadows of the Things That Will Be or of Things That My Be, Only; the finger points. We all read the name. Scrooge asks, with sorrow, “Am I the man who lay upon the bed?” His dialogue proceeds as written; he clutche the Spirit’s robes and finds himself hugging his own bedclothes.

Finney, sobered by the visit of Bob Cratchit to Tiny Tim’s grave, says, “Spirit, you have shown me a Christmas which mixes great happiness with great sadness, but what is to become of me?” The Ghost points to another part of the graveyard, where Scrooge reads a new stone. “No, no! Please! I beg you! I’ve seen the error of my ways! I’ll repent! Truly, I’ll repent!” The stone is gone, and a Death’s Head us revealed beneath the Spirit’s hood. Scrooge stumbles backward into a grave and, finding no bottom, falls and falls.

Matthau finds himself in a cemetery, and complains about a shadowed tombstone, “I can’t read the name.” The Ghost obliges with a flash of lightning. “No! It’s me! It’s Ebenezer Scrooge!” The suffering ghosts from earlier reappear around him, now singing “You Wear a Chain”. The tombstone rises briefly into a demonic face, and the spirits blow away. “I’m not the man I was! I promise to honor Christas in my heart and keep it all the year! Tell me I may sponge away the writing on this stone! Please!”

McDuck, realizing Tiny Tim is dead, cries “Spirit, I didn’t want this to happen! Tell me these events can yet be changed!” Just now, though, he notices two weasels digging a grave, laughing about the small, mean funeral that preceded this. When they go off on a break, Scrooge creeps forward. “Spirit, whose lonely grave is this?” The Spirit scratches a match to light another cigar; the light from this reveals the name. In case we failed to read this, the Spirit guffaws, “Why, yours, Ebenezer! The richest man in the cemetery!” He slaps Scrooge on the back, sending the miser tumbling into the grave. Scrooge snatches at a root. The casket within the grave shakes and burst open, belching forth flame. As the flames leap toward him, Scrooge shouts, “No no no! No! Please! I’ll change! I’ll change!” Scrooge finally falls into the flames, struggles to escape, and finds he is wrestling with his bedclothes.

Scott orders, “Take me home.” There is lightning and thunder; he is surprised to find himself in a graveyard. “I thought we’d agreed that you would transport me home.” The Spirit points. “Spectre, something informs me that the moment of our parting is at hand. Tell me what man that was we saw lying dead.” More lightning: it reveals a flat stone spattered wth snow. “No. No. Before I draw nearer to that stone, answer me this. Are these the shadows of the Things That Will Be, or are they the shadows of Things That May Be, Only?” His teeth are on edge; the Spirit points down. He steps forward and kneels slowly to sweep snow from the stone. He pauses to consider that men’s courses foreshadowing certain ends, and receives by way of answer only more thunder. He reads the stone. Now all but in tears, he exclaims that he is not the man he was; why show him this if he is beyond hope? The Spirit’s hand trembles. Smiling hopefully, Scrooge declares that the Spirit’s nature is interceding for him, and asks if he may yet change these shadows by an altered life. The hand is definitely shaking. Scrooge promises to honor Christmas in his heart, and live in the Past, Present, and Future. “Tell me…tell me that I may sponge away the writing on this stone!” He pleas, weeping openly now, “Spare me! Spare me!” He falls on the stone and wakes facedown on his bed.

With Caine, we go straight to the graveyard, a dark, snowy, windy spot encumbered by thunder and lightning. “Must we return to this pace?” There is no answer; Scrooge deduces, “There is something else I must know. Is that not true?” Still no reply. He turns to face the Spirit, “Spirit, I know what I must ask. I fear tom but I must. Who was that wretched man whose death brought so much glee and happiness to others?” The Sopirit points to a tombstone. Scrooge starts for it, but turns back and begs to know whether these are the shadows of Things That Will Be, or the shadows of Things That May Be, Only. The Spirit points again. Scrooge, slumping, steps stoneward again, only to turn back. “These events can be changed!” Coming to another stone entirely, he points as if to ask “This one?” The Spirit insists on the one it pointed to first; Scrooge won’t look, sobbing, “A life can be made right!” Snow has blown across the biographical data on the stone. Scrooge brushes it away and reads “Ebenezer Scrooge! Oh please, Spirit, no! Hear me! I am not the man I was; why would you show me this if I was past all hope? I will honor Christmas, and try to keep it all the year.” The speech goes on; he drops to his knees, clutching the Spirit’s robes. “Oh, Spirit, please speak to me!” He buries his face in the robes and falls forward.

“Spirit, tell me,” says Curry, “Can this cruel future be changed?” He walks into a foggy graveyard choked with trees. “Is this where that wretched man now lies underground?” The Spirit points. Scrooge, his gaze averted, moves to the stone indicated. He asks whether these are the shadows of the Things That Will Be, or only the Things That Might Be. When there is no reply, he goes on, “All lives lead to certain ends. But if our lives change, the ends must also change…right? They must!” The Spirit points. Scrooge moves to a standing stone; he can’t look. When his eyes finally do rise, he cries, “That lonely corpse was me? Oh, no! No! Don’t let me die unmourned!” He explains that he is not the man he was. “I will honor Christmas in my heart, and keep it all the year. I will learn from the past, I will live in the Present, and I shall hope for the Future! I will keep the three Spirits in my soul and remember their lessons always!” The Spirit points to the stone again. He reprises the declaration that he is not that man any more; why show him this if he is beyond all hope? “Tell me I can make a better future than this!” The Spirit vanishes. :All alone, Stranded.” He weeps. A bright light passes in front of him, and he is weeping on his bed.

After Stewart turns, he finds himself walking through a foggy and unpleasant graveyard. He inquires whether these are the Shadows of Things That Will Be, or of Things That May Be, Only. There is no answer. “Men’s actions determine certain ends if they persist in them,” he explains, “But if their actions change, the ends change too. Say it is so with what you show me.” The Spirit doesn’t move, pointing at a stone. Scrooge, guessing what he will find, doesn’t want to look, but finally turns his gaze down. Somehow, he is surprised. (Maybe he was expecting Tiny Tim’s gravestone.) “Am I the man who lay upon that bed?” The Ghost does not reply. “No, Spirit! Oh, no, no!” He shakes his head with horror and then turns to debate with the unspeaking Spirit, declaring he is not the man he was. “Why show me this, if I am past all hope? Ha!” The Ghost is not impressed. “Good Spirit, pity me! I will know Christas, in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. The Spirits of all three Christmases shall thrive in me. I shall not shut out the lesson that they teach.” Desperate now, he pleads, “Oh, let me wash away the writing on this stone!” The eyes of the Spirit have gone dark. The tombstone breaks apart, revealing an open grave underneath; the casket is open, to show Scrooge the body of Scrooge. The ground beneath his feet crumbles, and he falls face to face with his own corpse. Now the casket trembles and falls away; he and the body tumble. Hugging his own dead self, he goes into freefall, and then wakes, hugging his own bedpost.

FUSS FUSS FUSS #17: Tomb It May Concern

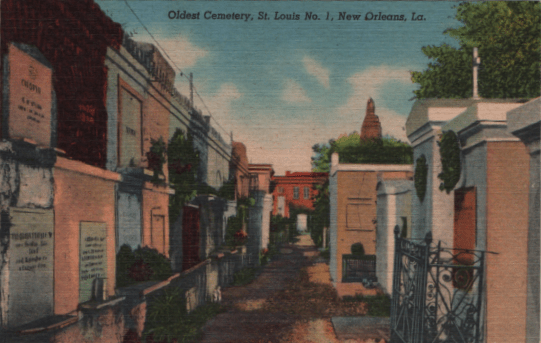

In general, we are transported to a graveyard suited to Dickens’s description, which was based to some degree on Highgate, London’s great burying ground, but also on any number of badly kept overcrowded burial yards of the day. The crucial stone is not especially described in the text, beyond the owner’s name. John Leech’s illustration in the original edition shows a small horizontal stone, and Scrooge IS described as crawling to it. That may have been from dread, of course: so a standing marker is not out of the question.

The filmmakers have suited themselves here. A horizontal stone is good for throwing oneself on, but Scrooge can cling hopelessly to a standing one. Most of the movie markers are exceedingly plain. Granted, no one would have paid a farthing extra to honor the late Ebenezer, but surely fashion in 1843 would have dictated a little scrollwork around the name, at least.

Flat stones are possessed by Hicks (whose marker already has the snow neatly cleared from the name), Rathbone, Finney, Scott, Sim I (an especially stark stone), Owen, and Stewart. Standing stones are bestowed on McDuck, Sim II, Caine, March, Magoo, Matthau, and Haddrick. By comparison, Matthau and Haddrick also show us Marley’s tombstone. In Haddrick, Jacob has a standing cross—surely more expensive than anything Scrooge would have sprung for—while in Matthau he has a standing stone with a rounded top (also an extra expense.) McDuck, the cheapest of the Scrooges, of course had HIS partner buried at sea.

Most stones show just the name: no epitaph, no date. Those who speculate on the death date take it for granted that the unrepentant, unyielding, unvisited by Spirits Ebenezer would have died on Christmas, in fact, the very Christmas Marley appears to him. This was to be his last chance, according to that theory. Sim I is afraid he is already dead, while the Ghosts who appear to Finney and Stewart reveal themselves as grim Reapers. But one or two versions give the miser extra time. Haddrick’s stone gives a death date of 1844. (His is also the only stone with a birth date, either 1765 or1785). Owen’s tombstone gives Scrooge until 1845. And since both these stories take place well before 1843, the date of publication, they seem to have intended Scrooge to go on as hardhearted as ever for a couple of Christmases.

INTERLUDE

Finney takes a quick detour at this point. It is dark. Scrooge wakes, not in his bed but in a casket-shaped depression on a red floor. He rises, not recognizing his surroundings and rather apprehensive. Some unpleasant odor reaches him; he rises from the hole. Following the aroma, he touches a red rock, which is burning hot. A laughing voice booms, “Ah! There you are!”

Scrooge recognizes the voice. He calls to the gloating Jacob Marley, “Where am I?”

“I should have thought it was obvious.” Marley explains he has come to escort Scrooge to Scrooge’s chambers. No one else wanted to.

They are running, for no apparent reason. “That’s very civil of you, Marley,” says Scrooge. “I am dead, aren’t I?”

“As a coffin nail.”

“I rather hoped I’d end up in Heaven.”

“Did you?” Marley, who is vastly amused, explains that Scrooge has been named Lucifer’s head clerk, to serve Lucifer as Bob Cratchit served Scrooge.

“That’s not fair!” Scrooge cries.

Marley admits to finding it “Not altogether unamusing”, and opens the door into a replica of the Scrooge & Marley counting house. This one is more frigid than the earthly one, being hung with icicles. Lucifer, Marley explains, has turned off the heat here, lest it make Scrooge drowsy. Scrooge will be the only one in Hell who will find it too chilly. He adds, as he is ready t leave, “Oh. And watch out for the rats. They…nibble things.”

Scrooge begs for mercy, and Marley steps back inside. He was forgetting something. Scrooge’s chain is on its way; Marley conveys the apologies of the management that it wasn’t quite ready when Scrooge arrived. Even Marley, it seems, underestimated its length and weight: extra devils had to be put on the job. Sweating executioners now bear a chain worthy of mooring an ocean liner and bind Scrooge with it. As he sinks under the weight, he begs Marley for help. “Bah!” Marley replies. “Humbug!” and adds, closing the door of the cell, “Merry Christmas!”

Still calling for help, Scrooge wakes again, now on his bedroom floor. His bedclothes have twisted around him, and he is choking. Perhaps this is how he would have died, without the Spirits, “gasping out his last”.