Scrooge’s former self grew larger at the words, and the room became a little darker and more dirty. The panels shrunk, the windows cracked; fragments of plaster fell out of the ceiling, and the naked laths were shown instead; but how this was all brought about, Scrooge knew no more than you do. He only knew that it was quite correct; that everything had happened so; that there he was, alone again, when all the other boys had gone home for the jolly holidays.

He was not reading now, but walking up and down despairingly. Scrooge looked at the Ghost; and with a mournful shaking of the head, glanced anxiously towards the door.

It opened; and a little girl, much younger than the boy, came darting in, ad putting her arms around his neck, and often kissing him, addressed him as her “Der, dear brother.”

“I have come to take you home, dear brother!” said the child, clapping her tiny hands and bending down to laugh, “To bring you home, hoe, home!”

“Home, little fan?” retorted the boy.

“Yes!” said the girl, brimful of glee. “Home, for good and all. Home, for ever and ever. Father is so much kinder than he used to be, that home’s like Heaven! He spoke so gently to me on dear night when I was going to bed, that I was not afraid to ask him once more if you might come home; and he said Yes, you should; and sent me in a coach to bring you. And you’re to be a man!” said the child, opening her eyes, “and are never to come back here; but first, we’re to be together all the Christmas long, and have the merriest time in the world.”

“You are quite a woman, little Fan!” exclaimed the boy.

She clapped her hands together and laughed, and tried to touch his head’ but being so little, laughed again, and stood on tiptoe to embrace him. Then she began to drag him, in her childish eagerness, towards the door, and he, nothing loth to go, accompanied her.

A terrible voice in the hall cried, “Bring down Master Scrooge’s box, there!” and in the hall appeared the schoolmaster himself, who glared on Master Scrooge with a ferocious condescension, and threw jo, into a dreadful state of mind by shaking hands with him. He then conveyed him and his sister into the verist old well of a shivering best-parlour that ever was seen, where the maps upon the wall, and the celestial and terrestrial globes in the windows were waxy with cold. Here he produced a decanter of curiously light wine, and a block of curiously heavy cake, and administered instalments of these dainties to the young couple; at the same time, sending out a meagre servant to offer a glass of “something” to the postboy, who answered that he thanked the gentleman, but if it was the same tap he had tasted before, he had rather not. Master Scrooge’s trunk being by this time tied on to the top of the chaise, the children bade the schoolmaster good-bye right willingly; and getting into it, drove gaily down he garden-sweep; the quick wheels dashing the hoar-frost and snow from off the dark leaves of the evergreens like spray.

“Always a delicate creature whom a breath might have withered,” said the Ghost. “But she had a large heart!”

“So she had,” cried Scrooge. “You’re right. I’ll not gainsay it, Spirit. God forbid!”

“She died a woman,” said the Ghost, “And had, as I think, children.”

“One child,” Scrooge returned.

“True,” said the Ghost. “Your nephew.”

Scrooge seemed uneasy in his mind, and answered, briefly, “Yes.”

The scene is particularly prone to pruning by people who want the story to move faster. Some screenwriters simply combine this Christmas with the previous one. (Dickens did so in his readings in public, as a matter of fact.) Others skip from the schoolroom to Fezziwig’s, without stopping for Fan, leaving us wholly in the dark about how nephew Fred and Ebenezer are related. Many make up for dropping these family strains and their effect on Scrooge’s personality by turning the apprentice Ebenezer, to be seen later, into a dour and serious lad, uninterested in Christmas.

That bit of business with the schoolmaster appears in none of the pictures described here; in fact, he has very little part in the story until we reach Caine.

Owen makes the two schoolroom scenes into one Christmas. The depressed young Scrooge is standing at the end of the previous scene when a servant announces, “Master Scrooge, your sister is here.” This Fan is a 1930s movie child playing at Little Red Riding Hood, perky enough for a Shirley Temple or two, but with a British accent. After Fan delivers the “Home, for ever and ever” speech, she goes on in some detail about the holiday food ad Wonderful Christmas to come. Young Scrooge exclaims, “God bless you, Fan!” twice. The older Scrooge and the Ghost reappear now, the Ghost observing “She loved you.” “She did.” “I believe she had children before she died.” “One child.” “Yes, your nephew.” Scrooge just looks at her. Realizing he has gotten the point, she says, “Come.”

In Sim I, a timid knock tells us something is about to happen. Fan peeks around the door and, seeing her brother, cries “Ebenezer!” She rushes in; old Scrooge runs to embrace her, and is devastated when she passes through him. After she delivers the “Home, for ever and ever” speech, ebenezer breaks in to object that their father hardly knows him, and observes that their mother must have looked much as Fan does now. Fan suggests this is why Father relented, and finishes that passage, adding that Ebenezer will never be lonely again “as long as I live.” He tells her she must live forever then; nobody else has ever cared about him, and nobody else ever will. When she tells him that’s nonsense, he sobs on her shoulder. “She died a married woman,” the Ghost observes, “And had, as I think, children.” “One child.” :”True. Your nephew.” “She died giving him life.” “As your mother died, giving you life, which your father never forgave you, as if you were to blame.” Scrooge simply gazes straight ahead.

In Rathbone we see a girl two or three years older than the boy; she slips in to slap a hand down on Ebenezer’s desk. “I’ve come to bring you home, brother Ebenezer!” “Home?” “Yes, for good and all. Father sent me in a coach to fetch you. We’re going to be together all Christmas long and have the merriest Christmas ever!” She has pulled Ebenezer from his seat and they are now dancing around the room. Eventually, she draws him outside. The Ghost gazes into the sky through most of the dialogue with old Scrooge. He turns to face Ebenezer only on the words “Your nephew, Fred.” Scrooge admits this, abashed.

Sim II ages the schoolboy at a desk to the apprentice at a desk in Fezziwig’s, bypassing Fan.

Finney’s Fan peeks in at the door and cries “Ebbie!” The scene moves quickly, but largely as written. The Ghost is stern reminding old Scrooge of “Your nephew!” Scrooge looks guilty as he says “Yes.” The Ghost then announces “Here’s a Christmas you really enjoyed.”

Scott’s version of young Scrooge at this point resembles Abel Gance as the young Napoleon. Fan is a brittle, large-eyed creature. “Eb” refuses to believe her when she tells him he’s coming home, and when he does come to believe it, he isn’t all that perked up by it. “Come,” his sister says, “We mustn’t keep Father waiting.” The older Mr. Scrooge is outside: he is abrupt, severe, and sour (if he’s so much kinder than before, it’s a good thing we didn’t see him before.) Ebenezer, he declares, will be allowed three days at home and then start his job at Fezziwig’s. Fan objects, but Mr. scrooge is immovable; we can see that he and Eb are not going to enjoy being home for the holidays. Old Scrooge’s face clearly shows he is not indulging happy memories. The Ghost is intent on driving home the moral of the story; she points out that Fred Holywell “bears a strong resemblance to your sister.” “Does he? I never noticed.” “You never noticed. I’m beginning to think you’ve gone through life with your eyes closed. Open them wide.”

Caine drops Fan but DOES include the schoolmaster, who is shown to be the inspiration of Ebenezer’s work ethic. We are also shown how the schoolhouse disintegrates, which is left out of other versions. As far as the traditional course of the story, we simply bridge to the next scene by noting that young scrooge is about to be apprenticed to a fine businessman.

In Curry, we see an older schoolboy throwing down his beloved copy of Robinson Crusoe, driven by his plight to scoff “Bah! Humbug!” at it. He looks out the window. Old Scrooge sighs “So many lonely Christmases.” The Ghost, subdued for once, replies, “Right. But not this one!” He points to the door as Fan flings it open, Old Scrooge runs to embrace her, but she passes through him. As she explains to Ebenezer why she’s there, he objects, “But Father….” “Oh, pooh on Father!” she cries. “I’M inviting you!” (Presumably she hired the coach with hert mad money.) The Ghost and Old Scrooge exchange remarks about her large heart; Scrooge recalls that they had a happy Christmas “in spite of Father” and goes on to wish that she was still alive, to invite him in for Christmas. “But she has!” the Ghost objects. “Her goodness lives on in Fred!” Scrooge smiles. “Yes. I wish….” Debit growls, and so does Scrooge, turning away. The Ghost suggests “Let us visit another kind soul.”

Stewart, watching his slightly older schoolboy self, seems to know who is coming (or has heard her theme music in the background.) He turns to the door in time to see “Fran” enter. Fran eventually takes her brother out to the coach and they ride for home, her head on his shoulder. Old Scrooge turns away from the scene, his face hard. “Such a delicate creature,” the Ghost remarks, “But she had a large heart.” “So she had. You’re right. I’ll not gainsay it, Spirit, God forbid!” “She died young.” “Too young.” “Your sister married and had children.” “One child.” “True. Your nephew.” Scrooge pauses. “Fred. Yes.” He seems on the verge of realizing something, but they walk on. Scrooge stops to stare.

FUSS FUSS FUSS #9: How Old WAS Ebenezer Scrooge?

Let’s talk this over. Why was young Ebenezer left to moulder at school over so many Christmases? Children were routinely sent to school away from home, of course; one suspects many of them were kept there as long as possible to keep them out from underfoot. (Day Care Centers have that problem with parents in our own day.) All Dickens tells us is that this had something to do with an unpleasant father. That, plus the fact that Scrooge’s mother is never so much as mentioned, has ;ed to a common tradition that Mr. Scrooge turned against Ebenezer because Mrs. Scrooge died in childbirth at Ebenezer’s debut in the world.

The difficulty with that theory is that Dickens clearly makes Fan younger than her brother. They COULD be half-siblings, of course, but most filmmakers prefer to swap their ages, or ignore the question altogether. (In the version Basil Rathbone recorded for Columbia Records in 1942, he explains that he is at school because his father doesn’t like children. Stewart states simply that his father turned against him when his mother died, without giving any cause of death for her.

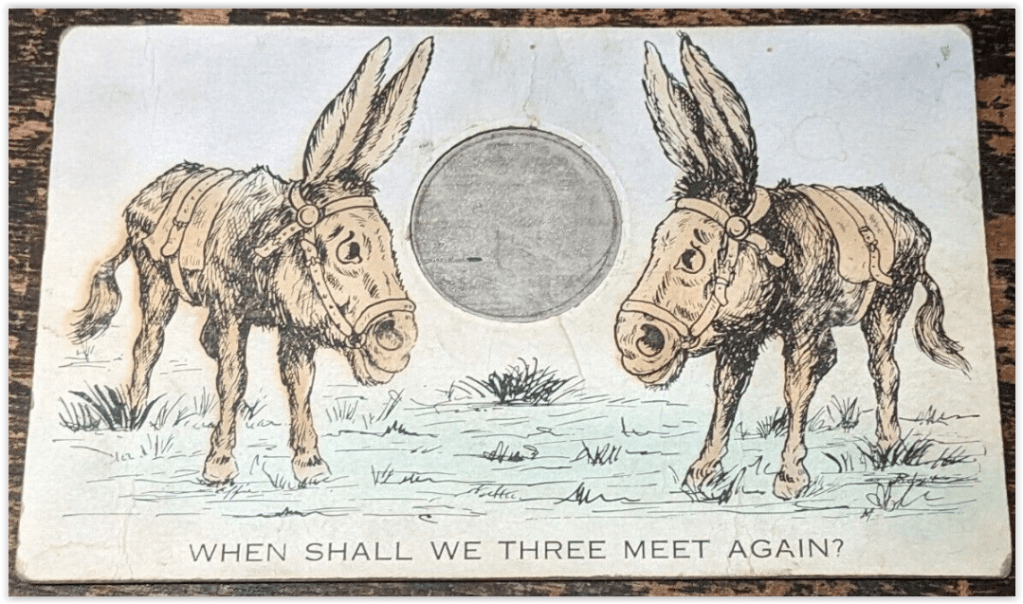

Now, most versions follow Dickens in giving us two different young Ebenezers: the younger one reading Robinson Crusoe and a somewhat older one reuniting with Fan. The first schoolboy generally looks to be between seven and nine. The Ebenezer of the Fan scenes varies more widely, with Stewart and Owen the youngest, at twelve or thirteen, Caine and Finney next, Curry well into his teens, with Scott and Sim I both sturdy young men. When Fan arrives she is almost always an exuberant, excited child, glowing with health and the spirit of Christmas, looking not the least bit frail. She seems to be two or three years younger than whatever Ebenezer she meets. The exceptions are Owen, where Fan can’t be much more than nine, and Sim I and Scott, who are the most definite about the death in childbirth theory about Mrs. Scrooge. In these, Fan might be a little older than her brother, or at least very close in age. (There’s another answer: maybe they were twins.)

Not that it makes any difference at all, at all, but the character of Fan was based on Dickens’s own sister Fan. She was older than Charles.