Do you know where we get the phrase “Peeping Tom” for a man who tries to get a look at women in a state of undress? Well, that’s a pity, because I’m going to tell you the story anyhow.

There are plenty of versions of the story of Lady Godiva. My favorite is Will Cuppy’s, though Dr. Seuss had an imaginative take on it. But, to summarize (go read Will Cuppy’s on your own time; it’ll make you forget about this one, another evidence of why HE deserved a Nobel Prize), Godiva was married to grumpy old Earl Leofric, and argued with him about taxes. The sheer repetition of her arguments drove him so crazy he finally told her he’d forget about taxes if she would ride through the streets of Coventry naked. Godiva was so dedicated to the cause that she did this, after first sending out a decree that everybody in Coventry had to stay inside and bar their windows. She went on the ride, the Earl remitted the taxes, and the only man who could testify to what had happened, a tailor named Tom who HAD to peek out of his window, was struck blind by the wrath of God. And everyone lived happily ever after, even Tom, who at least had his memories.

Both Godiva AND Tom inspired generations of readers. Naturally, there are all manner of objections to the story, beginning with a suggestion that shuttered windows hadn’t been invented yet, so Tom couldn’t have unbarred his, and running right through the inevitable suggestion that there was no Lady Godiva, that the whole story is simply a modern perversion of an old Celtic fertility rite. (When I have the time, I might go into the history of deciding every folk story is part of an old fertility rite, but the research would be vast. Or at least half that.)

Well, you will be relieved to know that there was indeed a Lady Godiva, and an Earl Leofric, too. Godiva is mentioned by name (under numerous creative spellings) in documents of the eleventh century, along with Earl Leofric, along with their children and grandchildren (she was the grandmother-in-law of King Harold II.) They gave a lot of money to religious establishments—one monastery claims Godiva signed their charter–and it is remarked by several researchers that in the century after Godiva’s supposed adventure, the people of Coventry did not pay taxes. (Except on horses, which is an interesting sidelight on the story, since Godiva was riding on a horse. Did the Earl bear a little bit of a grudge, perhaps?)

Unfortunately, the story of the naked ride does not turn up until two hundred years after it was supposed to happen, and TOM does not turn up for another five hundred years after that. The bit about the taxes is supposedly attested to by a stained glass window of the fourteenth century, but that has inconveniently not existed for a few hundred years, and didn’t allude to the nudity. There are extreme skeptics, in fact, who feel the whole naked bit was promoted by Protestant reformers to discredit a devout Catholic (Godiva owned one of the earliest known rosaries), OR by the town council of Coventry to drum up tourist trade. One or two people, too conservative themselves to consider a lady riding out dressed only in her long hair (which supposedly covered her to the ankles) insist that she was probably wearing tight silk, or was clad only in her shift, like someone doing public penance. This would, of course, kind of contradict the whole fertility goddess business, or the more modern concept that this was all just a metaphor for wives using their bodies to get their husbands to do stuff.

The question of when and why Tom was added to the story is a subject for dozens of other studies. He and his peeping might have been known long before the story was written down: a bill to refurbish a statue of him shows up a generation or so before the first printed account. I admit to a little curiosity about what this statue, used in the annual Godiva procession, looked like in the early days, but the best I can learn is that it showed a man looking out a window. AND, according to people who don’t tell me why they think so, was probably not originally named Tom. In early versions of the story, Lady Godiva’s decree said anyone who peeked would be put to death, and that’s what happened to him. Whether he was executed on her command, or on Earl Leofric’s, or by that bolt from the blue, or by irate citizens of Coventry varies on the version told. Only later was he struck blind, which seemed to the literary set a more reasonable punishment for peeking. (Though Frederic Wertham might have had more to say on the subject.)

The best I can learn about why he joined the company is that the writers, being suspect in any case, have always added comic relief to the most intense dramas (medieval religious plays frequently include a few drunks, or a cranky old man, or somebody else to lighten the load.) Oh, and nobody has told me why he was a tailor. Early stories made him a groom in the Earl’s stable, which maybe eliminates the necessity of a window, but DOES bring up all sorts of side issues. Did nobody help Godiva into the saddle when she set out? Why weren’t THEY blinded? Or did the servants, who would probably have been used to seeing their bosses in the buff, not count? Tailors do seem to get a lot of coverage in folktales, but, again, this will have to wait for a whole nother blog.

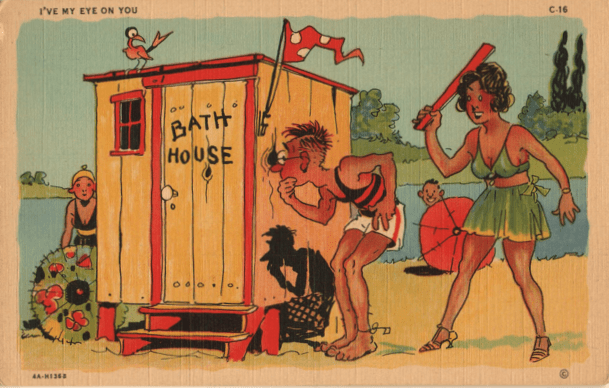

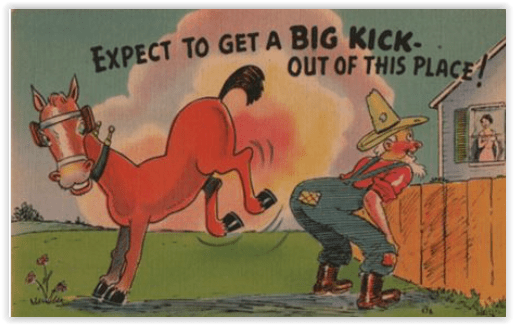

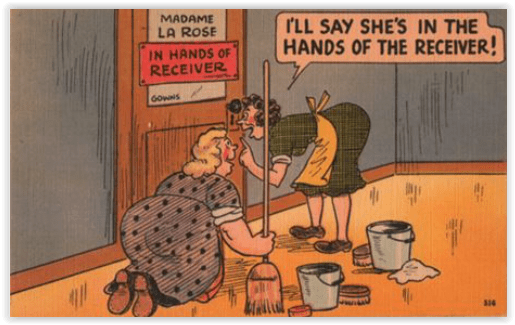

Anyway, this is why we call ‘em Peeping Toms, even if they happen to be female. In our next thrilling episode, we will consider the question more, but this time, I promise, we’ll talk about the postcards.