A power of years ago, but not so far from Fairview, there lived a fool named Egbert. Egbert was a good, honest fellow, understand: a man who grew vegetables on his little farm, went to services of a Sunday, and never fought with his neighbors. He was just not so very clever. Everybody knew that.

“Egbert’s a good lad,” the neighbors said to each other. “But he’s one of those who doesn’t know enough to pull his head in before he shuts the window.” They said things like this to Egbert’s face now and again, too. Since Egbert had never been anything but a fool, he didn’t feel bad about it.

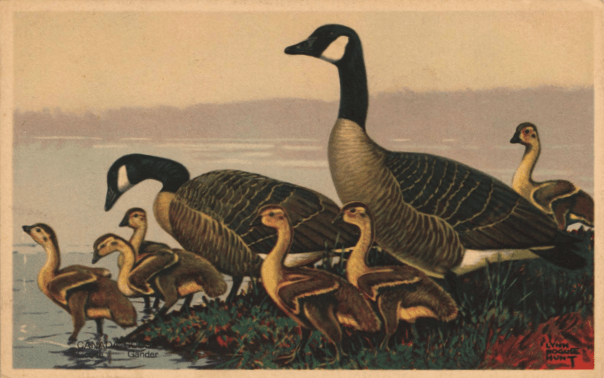

“It’s just as well I am a fool,” Egbert would say while he walked around with a salt shaker trying to catch wild geese by tossing salt on their tails, “Seeing as how that’s all I know how to do.”

One Sunday, Egbert was in church and the good reverend fetched a powerful sermon to the people about the proper care of their souls./ “The forces of this world will always try to steal the souls of good folks,” he said. “Your soul is in danger from all sides, from high and low. You can be poor and find money. You can be sick and get well. But once you’ve lost your immortal soul, it’s the last drop in the jug.”

The good reverend went on for some time about the sad, sorry life to be had by those who lost their souls, until Egbert was quite thoroughly horrified. “I really must take better care of my soul,” he told himself. “In fact, first thing tomorrow morning, I’ll put a lock on my front door.”

That afternoon, however, he attended a wedding party in town. It was quite the wedding for the groom was the son of the second richest landlord in the county. The King, of course, was the richest landlord in the county, but the King had no sons, so even Egbert could have told you none of them could be grooms. Still, even the second-richest landlord had food and drink aplenty for everyone, even Egbert who, being a fool, always ate and drank too much.

He felt simply terrible the next morning, of course. “Oh, my head hearts and my stomach hurts and both my legs hurt. If I had three legs, I’d feel sorry for me, because they’d all three be hurting. I wonder if maybe I’ve lost my soul. The reverend said people who lose their souls are perfectly miserable, and I don’t suppose miserable could get any more perfect than this. Oh, me!”

The pain in his head made it hard for him to get up, but get up he did. “I’d better find out what I did with that soul,” he said, “Before somebody steals it. Oh, my toes and little fingers!”

He looked on his windowsill first: that was where he generally threw his shirt at bedtime. Just as he looked up, one of the wild geese that used to come around his farm reached in and snapped up a little piece of wedding cake Egbert had dropped the night before.

“My soul!” screamed Egbert. “You are eating my soul! Give it back this second!”

The goose hissed at him. “Talk back to me, will you? I’ll teach you!” Egbert ran right out of the house, without his shoes or shirt, pausing only to pick up his trusty salt shaker.

The goose flapped long goose wings at Egbert. Being a fool, Egbert wouldn’t take warning. The goose was not at all used to people running at him when sensible persons would have known better. Fluttering backward, it hissed again.

“See here!” snapped Egbert. “All this is hurting my head! Just give me my soul back ad I won’t ask for a feather more!” He walked forward, not even noticing he was walking right across his rhubarb plants.

The goose decided to look for food elsewhere. With a “Honkkkk!” it flapped up into the sky.

“No!” cried Egbert, tripping over the early peas. “Come back with my soul!”

Doing his best to follow the fast, crafty goose, Egbert ran through his garden and right down into the town. He tripped over stones, ran into clotheslines, and stepped on cats. A few dogs chased him, but when they noticed he wasn’t paying attention at all, they quit. Some silly fools just didn’t know how to play, they decided, slinking back to their doghouses.

The goose eventually tired of all this, and settled to rest a moment in the yard behind a little yellow house. By great misfortune, this happened to be the home of Stanley, a pillowmonger who was fast and crafty, and hungry as well.

“Ah!” he cried, leaping out to get a hand around the throat of the goose. “You’ll make pillows AND supper!” Without asking whether the goose wanted to do either of these things, he dragged the big bird across to his chopping block and whacked its head off.

Egbert had seen the goose go to land and reached Staley’s yard just as Stanley was holding up the bird. Egbert’s eyes grew big as bird’s nests.

“My…my…my soul!” he whispered, for he was nigh out of breath.

“My goose,” said Stanley, catching up the axe again just in case. “It was in my yard. You can’t have any.”

“I don’t want a goose,” said Egbert, swaying back and forth in despair. “I’m not such a fool as that. I just want my soul!”

“I see,” said Stanley, who didn’t see ay all. “Your soul, is it? And what might your soul have to do with this goose in particular?”

Egbert pointed at the limp bird. “That is the goose that ate my soul just as I went to the window. It wouldn’t have been so bad if it had eaten my shirt, since I’ve got three shirts. But I have only one soul, which the goose ate. And now you have killed it!”

“Ah!” Stanley nodded. “That’s what it was, then.”

Egbert had been looking for a place to sit down and cry, but now looked straight at Stabley. “What what was?” He decided he liked the sound of that enough to say it a few more times. “What what was what what was what what was?”

Stanley set the goose down. “Just before it died,” he told Egbert, “This goose laid a beautiful egg. It was so beautiful, in fact, that it must be your soul. I thought at the time this was an egg beautiful enough to be a soul, and wondered what a goose would be doing with it.”

“My soul is in an egg?” Egbert demanded. “How wonderful!”

“Wait right here and you can take a look.” Stanley went into the house and brought out an egg he was planning to cook for breakfast. “This is it.”

“Oh!” cried Egbert, reaching for it.

“Careful,” said Stanley, drawing it back. “It’s raw, you know, and I won’t have you breaking my egg.”

“Your egg?” said Egbert. “But that’s my soul!”

“That may be,” Stanley told him, “But the goose laid this egg in my yard, and it’s quite a beautiful egg. You may not know this, but I am quite a fancier of beautiful eggs. I meant to keep it and put it above my fireplace as an ornament.”

“Oh, but I must have my soul!” Egbert cried, wringing his hands. “Couldn’t you give me that egg and let the goose lay another one?”

“I have killed the goose,” Stanley reminded him. “It won’t be laying any more eggs. Or souls. But if you like, I might be able to sell it to you. If you have enough money, that is.”

Egbert gave Stanley all the money he had in his pockets. Then he ran home to get all the money he had, plus two very nice rhubarb plants. “Now may I please have my soul?”

“You may,” said Stanley, bowing as he handed over the egg. “But be careful. You might drop it and break it before you get it home to eat it.”

“Eat it?” Egbert demanded, cradling his soul in his arms.

“Of course, eat it,” said Stanley. “You want your soul back inside of you where it’s safe, don’t you?”

“Oh! Yes!” Egbert nodded. “Thank you so much. I might not have thought of that. I’m such a fool I might have left it sitting where a dog might eat it next.”

Stanley nodded. “Or it might have gone rotten. Pity to have your soul spoil.”

“I shall take it home and eat it straight away,” said Egbert, and started to run back to the farm.

He had not gone far when he tripped on a small rock. This hurt his toes something considerable, for he was still barefoot, but what took his breath away was that he had nearly dropped his soul. When he could breathe again, he began to walk very slowly, keeping both hands, and both eyes, on the egg.

Of course, with his eyes on the egg, he couldn’t watch his feet. When he stepped on the grey cat’s tail, they both jumped into the air. The cat ran away. Egbert stood clutching his egg.

“I don’t think I can carry this all the way home without dropping it,” he thought. “Whatever can I….”

In running, the grey cat had bumped somebody’s garbage, and a tin can fell loose now and rolled into the roadway. “Oh oh oh!” cried Egbert. “I know! I don’t have to walk all the way home to cook an egg.”

He caught up the old can and ran to a nearby horse trough, where he filled it with water. Then he found a sheltered spot next to a high white wall. There he built a fire.

Over this fire he carefully hardboiled his soul, watching it every moment. He had listened to the good reverend for a good many Sundays and knew that the last thing anyone wanted was to have their soul burn.

After a good length of time, Egbert carefully poured all of the water out of the can, being not such a fool as to put his hand into boiling water. Then he tipped the can so the egg fell out into his free hand.

“Aieeeee!” he screamed, being just such a fool as to hold an egg which had just been boiled. His hand jerked up, throwing his hot soul over the wall and into the yard behind it.