Kerrin lived in the city of Sartain, and she liked it. She would write letters to her relatives who lived in the country, asking why they didn’t move to a nicer place.

“Everything in the city is clean and modern,” she wrote. “We have nice, solid rick buildings with none of your thatched roofs to let in the rain. We have gas lights in every room. There’s no need ever to walk out in the rain, for there are cabs pulled by strong horses to take you wherever you want to go. Our druggists have the newest pills and powders for fever, but I suppose your country doctors have nothing but tansy, sassafras, and pleurisy root. How can anyone live out in the middle of nothing, using dirt roads, with animals running every which where, when there are clean modern cities?”

A letter arrived one day to tell Kerrin that one of her relatives had passed away in Noverra, a village way out in the farmlands of Noverrashire. There was no question of Kerrin going that far out into the country to live, of course. But she thought she might just journey to Noverra to take a look at the house.

“People in the country are so backward,” she told her friends. “What can they know about buying and selling? I’ll tidy up the house and get a good price for it.”

Kerrin made most of the trip on a fast, powerful steam-powered train, but the train didn’t go to a town as tiny as Noverra. She had to ride some of the way on a crowded old-fashioned stagecoach. To get from the coaching station to the house, she had to ride with one of her new neighbors, a man named Lars, who had come to the station to meet her, bringing his wife, Joniel, and his six children in a farm wagon.

Kerrin wanted to be friendly. (Lars and Joniel might be willing to buy the house from her.) So she thanked them very politely for coming to fetch her, and set a handkerchief down on the board seat of the wagon before she sat down. Joniel asked if she had had a nice trip, and was obviously amazed that someone could travel that far from home and not be half dead from the excitement.

They spoke of this and that. Trying as she was to be nice, it was nonetheless not long before Kerrin had pointed out that the old-fashioned wheels of Lars’s farm wagon were broader and less elegant than those on city cabs. The city cabs moved faster, too, since their horses weren’t so fat from being overfed. A little later, she observed that children in the city wore shoes and certainly never ate apples which had fallen from trees by the road, with who knew what sort of dirt and insects on them.

“Oh!” she said, while looking at the trees. “What’s that? That sound?”

“Sparrow,” said Lars, who didn’t seem to say much.

“On that branch,” Joniel said, gesturing to one of the trees. “Do you see him?”

“My, he’s a little thing!” said Kerrin, looking the bird over. “In the city we have good, big healthy pigeons.”

Joniel and Lars listened to everything Kerrin had to say about the city, and the children listened to a lot of it. This was partly because they wanted to be polite (the lady from the city might be willing to sell them the house) and partly because not a one of them had ever been to the big city, and they wanted to hear all about it. Kerrin was more than willing to tell them, and she liked to be listened to. So she really had a nice ride, despite having to sit in an open cart with a dirty floor, until they reached her house.

“Oh, my stars!” cried Kerrin.

Aunt Malda’s cottage was just what she’d feared: a poky little thing with whitewashed walls of uneven stones, and a roof made of straw, The inside was worse: small and dark. There were no gas lights, of course: only a rusty amp that smoked and a few stubby candles. Things sat every whichaway on tiny shelves.

“And I’ll have to sweep all this dirt off the floor first thing!”

“I don’t like to tell you what to do,” said Joniel, who had come into the cottage with her. “But I believe I ought to tell you that this is a dirt floor.”

Kerrin stared at her neighbor in horror and then hurried to the back door. “They said there was a garden.”

It was no garden, so far as Kerrin was concerned. Gardens were neat little squares behind your house. This was much too big for a proper garden: it looked like an acre of plants or more. How had Aunt Malda managed such a thing?

At least it was tidy. The pants did grow in straight rows, or little squares, each plant in its proper place. Kerrin wasn’t sure what some of the plants were, but she had brought along a book on farm plants to read in the evenings. Yes, she thought: a very neat and pretty garden, if you overlooked the unsuitable size. All that spoiled the neat arrangement was one twisted little tree, standing by itself in the middle of everything.

“That will have to be cut down at once,” she said, pointing her parasol at it.

Joniel stared at her. “What? Are you serious? I….” Then she laughed.

“I don’t believe I said anything funny,” Kerrin told her neighbor.

“But….” Joniel stopped and took a quick look around the garden, though she could see very clearly there was nobody there. Then she leaned in toward Kerrin and whispered, “That’s the fair folks’ thorn tree.”

Kerrin frowned. “The what?”

“That tree belongs to the fair folk.” Joniel looked over her shoulder and, leaning in closer, whispered even lower, “The fairies.”

“Well, of all the nonsense!” said Kerrin, and now she did laugh at her neighbor’s joke. “Aunt Malda may have been backward enough to have a dirt floor, but even she couldn’t have believed….”

But Joniel was not laughing. “Every house in this quarter has a tree for the fair folk.” Her tone was serious. “That way, they’ll not bother the rest of the garden. And it’s best to put milk on the back doorstep, so they don’t come in and upset the house.”

This was very foolish. Kerrin thought about finding an axe and cutting the tree down there and then. But she realized this was exactly the sort of thing she had expected from people who lived in the country. And, after all, if every cottage around here had to have a thorn tree for the fairies, she wouldn’t be able to sell Aunt Malda’s house without it.

“No, I won’t cut it down,” she told Joniel, who looked relieved. “It’s pretty enough, in its way, and it may have its uses.”

“It does have uses,” Joniel said, again looking left and right as if expecting a fairy to leap at her from the dirt. “But the fair folk are using it.”

“Mmmmm,” said Kerrin. She decided she would not tell this woman her opinion about leaving milk outdoors at night.

Next morning, Kerrin set to work putting Aunt Malda’s cottage to rights. It was not easy work, even for a woman like Kerrin, who liked to keep busy. Water had to be fetched from the creek at the far end of the garden, and all Aunt Malda had were two small buckets with rusty handles. In the city, he burned coal to keep warm, but Aunt Malda had not even used wood, just old-fashioned peat. The only wood in the house was the furniture, and Kerrin decided she probably shouldn’t burn that, though burning was all most of it was good for.

Joniel came over to visit nearly every day, bringing over some milk or a cheese, and chatting about what a lovely cottage this was, and what Kerrin might expect for it, should Kerrin ever think of selling it. She never stayed long, because she had her own cottage and garden to care for, not to mention all those children.

She dropped by very early one morning, when Kerrin had just finished doing the laundry. That turned out to be a horrible job, with all the water to haul, and then heat over peat in the fireplace. If Aunt Malda had at east owned a nice modern stove…but no, there was just the fireplace, with all kinds of hooks and metal brackets Kerrin didn’t recognize.

Hooks were set in the walls of the cottage as well, and there was a rope that was obviously meant for a clothesline. Kerrin refused to hang her clothes to dry inside. The cottage was still dusty and dirty, and she was sure something like bats or mice lived in the roof, making noise the whole night through.

Instead, she took the clothes outside. A light breeze blew through the garden, and this would likely dry the clothes in no time if they could be hung on something. The thorn tree, standing all alone, was perfect/ It was neither especially neat nor especially modern to be hanging laundry on a tree, but the clothes would not need to be there very long.

Kerrin had set the last of the garments on the tree when Joniel walked into the garden, saying, “I came to ask….” Then Joniel stopped, and stared.

“Is that safe?” she asked. “I’m sure the…the fair folk hang their own laundry there.”

“I decline to believe any such thing,” Kerrin informed her. “And in any case, why should your fairies have the same wash day I do?”

Joniel looked around the yard. “I’m sure they….”

Kerrin sighed. “Ket’s go inside for a cup of tea. I have any amount of hot water left over.”

“Oh, I can’t stay,” Joniel told her, “I only came over in case you didn’t know about the fair, and needed a ride into town.”

“Fair?” said Kerrin. “No, I didn’t know.”

“That’s why I’m dressed up,” said Joniel.

Was Joniel dressed up? All Kerrin could tell was that her apron and bonnet were a bit whiter than the ones she wore every day, while her face and hands were clean for a change, Her eyes were shining. The fair was something special to her.

Kerrin didn’t especially want to visit some little country fair where she would no doubt be surrounded by smelly chickens, goats, and pugs. If she did go, she didn’t want to ride in a dirty old farm wagon.

“I’ll wait ‘til my wash is dry,” she told Joniel. “You folks go ahead. I can walk to town.”

“Are you sure?” said Joniel.

“Oh yes,” said Kerrin. “You go ahead.”

“All right,” said her neighbor, and ran back to join the family in the wagon.

Kerrin walked inside and started the tea. The more she thought about it, the more she thought that, unpleasant as it might be, a fair was just the place to meet people who might buy Aunt Malda’s cottage and garden. Oh, she knew Lars and Joniel wanted it, but she didn’t suppose they had enough money. People with money weren’t so backward as to believe in fairies.

Supping her tea, she stepped out ito the garden to check her clothes. Nearly everything was dry; she had known the breeze would take care of this. Wind banged the shutters all nifgt olong on the cottage windows, but it was good for something, She gathered the garments and took them inside, to pick out the best things to wear to the fair.

She was sorry she had not brought her new hoop skirts from the city. But it would be wise, she supposed, not to look TOO much nicer than everyone else. People might be too impressed to come up and talk to her.

Still, she had to look her best with what she had brought. Kerrin picked out the whitest of her petticoats, and the green dress that went so well with her hair. She pinned the skirt and the outermost petticoat above her knees, to keep them from being soiled as she walked along the dusty country road. When she reached town, she could remove the pins to let skirt and petticoat down. Spying a little smudge on her right shoe as she was pinning the petticoat, she took out a handkerchief and wiped it clean, muttering “Dirt floors!”

Now she needed something for her head. The cottage was, as always, dark inside, but she spied a green bonnet on top of the clothes she’d brought in from the thorn tree. She could not remember this bonnet, but there it was, and the perfect shade of green to go with her gown. Picking it up, she could smell the country breeze in it.

Tying the strings of the bonnet under her chin, she stepped out of the cottage. What a glorious day! She took a deep breath. The wind blowing across the garden smelled all warm and green. As ever, the road was dry and dirty, but Kerrin liked it. And the breeze was beautiful. City breezes smelled of dust, brick dust from all those brick buildings, or coal dust from the chimneys/ There weren’t enough trees there for the breeze to pass through.

Noy far from the cottage, the road passed through a small grove of trees. Kerrin had never walked there before, for fear something would drop on her from the branches. Now, though, she skipped right on in, singing “La la la la!”

“What a great tree!” She stopped in the middle of the grove to look around, and patted the trunk. “Hello, tree!”

Looking up, she found a squirrel staring down at her. “Hello, Squirrel! Are you hungry? You look hungry. In the city, people throw food to the squirrels. Why don’t you come with me to the fair and I’ll throw you at the food!”

The squirrel did not answer, so Kerrin decided to climb up and talk it over. Climbing would be awkward with these shoes, so she sat down in the road and took them off and then, throwing them her left shoulder, she started up the side of the tree.

Of course, the squirrel was not on the branch when she reached it. She looked around, but there was no squirrel to be seen.

“If these untidy branches weren’t in the way,” she pouted, “I could see things.” So she set about braiding the branches to make nice, even rows. Before she had finished more than three, though, she spotted two birds’ nests.

“Now, look at that!” she cried. “One nest has three eggs and one has five. This is highly untidy!”

She reached into the second nest to take out an egg and add it to the other so the nests would be even. But before she could do that, she spotted a feather on the edge of that nest.

“Here’s the thing for wearing to a fair!” she squealed. She looked around the sides of both nests but there was only the one feather.

“It doesn’t matter,” she declared. “These leaves are very much the same shape.” At once she tore leaves from the branches, stuffing them into her collar and cuffs. Once she had as much as she could hold there, she tried sticking them to her sleeves and face and bright green bonnet.

Those leaves just fell off. “Now what?” she demanded, swinging her legs over the branch. “Oh!”

From up here, she could spy the creek that ran from behind her garden through the grove of trees. The water seemed quicker here, and possibly deeper. Tall banks of mud rose on each side of the stream’s course.

“Mud!” she cried. “Just the thing for leaf-feathers!”

Jumping up, she ran along the branch until she was nearly over the mud. When she reckoned she was close enough, she bent her knees and jumped. Branches tore at her clothes, and one of her sleeves came right off. Kerrin didn’t mind. She landed, sitting down, on the mud at the very top of the bank.

“Whee!” she cried, sliding through the mud right down into the stream. Putting her head under water, she took a long drink.

There was plenty of mud to smear all over her face and clothes. She found a big hole in the bank, and dug into that for a while. Nobody seemed to be at home.

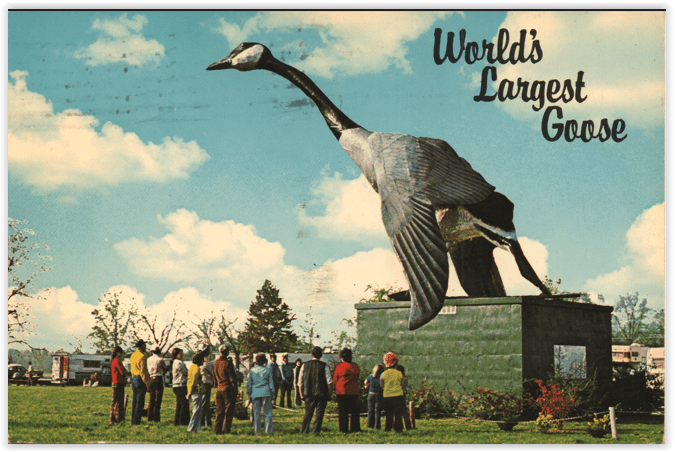

She climbed through the mud back to the road. On the way to Noverra, she said hello to some very interesting snails, a friendly snake, some cheerful beetles, and, of course, a butterfly. A grey goose flew overhead, but she knew it was too far away to hear her.

After checking out another empty hole along the road, she noticed that most of her leaves had actually fallen off during her climb up the bank. “There’s only one thing to do about that,” she announced, and climbed another tree to get some more.

Swinging from branch to branch, she plucked a few leaves here and a few there, giving her a nice variety, until she reached the end of the woods. This was also the edge of the village. Kerrin jumped from the last branch, did a little somersault on the road, and sat up to look over the village.

The village was very pretty, and she heard music. She coughed. The dust of the road had a nice color, and looked striking against the darker mud, but there was a wee bit too much of it. If she could have some water…only the creek was way behind her in the woods.

Not far away, though, she spotted a huge trough where people who brought their horses into town could get them a drink. “Just the thing!” Kerrin cried. “I’ll get a drink and wash off some of this extra dust while I’m there!”

Several people came over to watch as she stepped up to the trough, unbuttoning her dress. She saw Lars and Joniel among them, and waved. “I’ll be with you in just a minute!”

Her hand brushed the strings of her bonnet. She undid those and took it off.

Kerrin stared at the bonnet in her hands. This wasn’t her bonnet. Was it one of Aunt Malda’s? She didn’t remember having a bonnet like this at all. Well, no matter. She needed to finish dressing so she could go to town. What else did she need to put on?

She glanced down at her clothes. “My heavens! What happened?” She was amazed at all the dirt: she’d have to get dressed all over again! WHY couldn’t Aunt Malda have had a nice, modern wooden floor> She reached to pull her dress from her shoulders. She paused.

This dirt was not the same color as the dirt of the old floor. But maybe that was because the sun was shining on it. The sun?

Looking up again, she saw the crowd of people watching her. In the same moment, she realized her dress was unbuttoned, and torn to scraps anyhow. Twigs and leaves and other garbage were stuck all over her. The only clean garment she had seemed to be this strange bonnet she still didn’t recognize. Where had it…. Oh, yes. It had been with the clothes she had dried on the thorn tree.

Her mouth dropped open. Turning, with a shriek she ran right back to the cottage, never slowing down for a second. Slamming through the front door, she sped out the back, and burst into the garden.

“Take it back!” she screamed, and hurled the bonnet at the thorn tree.

The bonnet flew into the sky and was gone. Kerrin looked around the ground to see where it had fallen. But it had vanished as if it had never been. Exhausted, she sat down on the back doorstep.

“Owww!” she cried, jumping back up. She had sat on an empty bowl. She knew very well she had not put a bowl on the doorstep.

In the end, Lars and Joniel bought the cottage and garden. Kerrin did not wait around to argue about the price. She left for Sartain the day after the fair.

“How brave of you to stay for so long in the country!” said her city friends. “Why, the people in that dreary little village probably can’t even read or write!”

“Maybe not,” said Kerrin. She shuddered. “But for all that, some of them know a thing or two worth remembering.”