The First Golden Age of Postcards, when the fad was at its peak and millions of these little analog text messages were selling every year, roughly from 1907 to 1914, saw a growing public notice of the movement of women into the work force. Women had always kind of BEEN part of the work force, but these Modern Women were starting to challenge men for traditionally male occupations instead of keeping to their place behind a needle.

This train of thought was suggested to me by the arrival in my inventory of three postcards featuring this obviously female and slightly threatening barber. The set, possibly part of a larger series, emphasizes the pleasure of a male customer at being attended by her staff of female attendants.

In fact, though we see here that women could be employed as bookkeepers as well, neither the postcards of the 1910s or their descendants in later decades were out to prove women could do a job as well as a man. The postcard companies were more interested in selling postcards than in making a point.

The best that could be said of them was that they accepted that women DID do jobs associated with men. The jokes told by the artists involved weren’t about whether they should or could, but about finding a saleable gag to go with the job.

World War II gave momentum to the movement of women into the work force, and the WAC postcards The woman soldier was a hard sell in some markets, but the postcard artists did their best to show how much they had in common with their male counterparts. (Sleep, for example: the most precious commodity for any soldier. One WAC told me you didn’t waste these opportunities. In fact, she said, you didn’t even notice them: a second after your head hit the pillow, the bugle blew.)

The war’s effect on farm labor was also well documented.

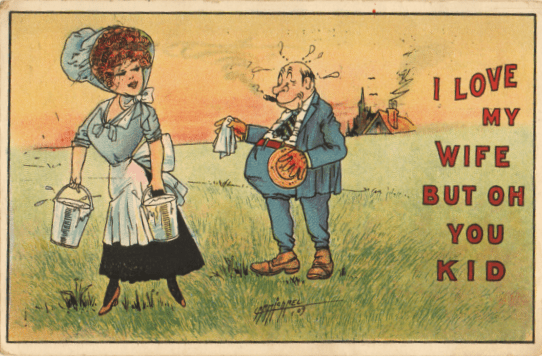

Though in fact, the farmer’s daughter and the pretty milkmaid were staples of literature, postcards, and jokes long before the war.

It continued during the War as well.

And, odd though it seems, even the female blacksmith predates that war.

Like the male blacksmith, female blacksmiths did have to move away from horses and toward horseless carriages as time went by. Postcard artists may have been more interested in showing off an attractive pair of legs than meditating on the social phenomenon they represented.

That legs sold more postcards than sociological meditation on the role of women in the workforce was simply an occupational hazard.