In olden days I was acquainted with a young lady I refer to as the Dumpster Cinderella. This is not the place to go into ALL of her qualities and quiddities, but one of her goals in life was spreading the word about Real Jazz. This was a musical form which she felt ceased to exist around 1932, when jazz went all new-fangled. She wrote articles (or, more often, article-long letters to editors) and took her recordings and her message to any audience which would listen. She succeeded beyond her hopes with high school music classes. She found the kids genuinely interested in music new to them: they asked intelligent questions, and inquired where they could find more Real Jazz.

So she frequently did follow-up lectures, with recordings the kids hadn’t heard the first time. And she came to me once with a problem. Not to ask my advice, since, as usual, she had made up her mind, but simply to add strength to her own arguments.

“Some of these songs are really raw,” she told me. “The performers were way too frank about race and sex, especially sex, for me to play these for high school students.”

“I don’t know how much rap and hip-hop you listen to,” I said, “But I have a feeling they won’t learn any new words.”

“Oh, these are instrumentals,” she assured me. “But I don’t dare play them because the kids could look up the lyrics online.”

It is easy to make fun of the Dumpster Cinderella (believe me) and her caution, but I have, in my hunt through archaeological comedy, run into similar warnings and cautions. Leafing through a college newspaper of the later nineteenth century, I found a note that although they welcome articles and stories written by students, they would not tolerate the use of terms like “Shucks”. I was taken aback by this, as the term in my own day was used by comical backwoods types. Gradually, the reason dawned on me.

“Shucks”, like “Shoot”, which I found banned in other periodicals, is a euphemism for a biological product found frequently by the roadside in that distant century of horse-drawn vehicles, but never never mentioned in polite society. And on the principal that everybody who saw “Shucks” would know what word was meant, the euphemism was banned too.

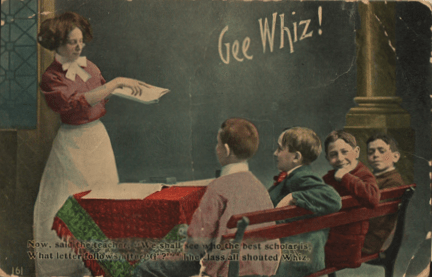

In my own time, I had teachers who reacted with horror to children who exclaimed, “Jeez!” In their ears, this was profanity, as it was short for a longer sacred name. The same was true in some postcards I have received, which are a little cagey about using the exclamation “Gee!: a similar abbreviation, or simply short for “God” (a word that couldn’t, like “Devil”, be used on many radio networks through the middle of the twentieth century.)

Banning these cover-ups was slow in leaving us. Walt Disney’s Pinocchio received token resistance when it referred to the nameless cricket character by a similar euphemism. By my time, in spite of teachers who banned “Jeez”, we sang “Blue Tail Fly” in music classes without a hint that the phrase “Jimmy Crack Corn” was anything but a nonce phrase like those Fa La Las in “Deck the Halls”. Of course, with our steam-driven cell phones and no Internet, we had no place to look this up.

Nowadays, as we move further into the age of dysphemism, in which we not only avoid using euphemisms but try to come up with an even more offensive phrase, I wonder what will happen to the poets of euphemism, those folks who preferred to bellow “Fudgesicles! Drippy, sloppy fudgesicles!” and “Well, goshdang the goldarn thing!” Or will some musical combo decide to write bold brave songs using once-banned terms like “Gee whillikers” and “Shucks”, and start a whole new trend in rock, rap, or even Real Jazz? (Dibs on the Fudgesicle Blues.)