When I received THIS wordy postcard, I checked, as I usually do, to find out how many other examples were for sale on eBay. Hoo boy, as they say in Paris. There were at that moment 1183 postcards featuring the Legend of Spanish Moss, at prices ranging from low to exorbitant. There was a vast variety of pictures, so I persevered in hopes that MY picture happened to be a rare variant worth its weight in lottery tickets.

The postcards were far from uniform in telling this particular tale. Allowing for abridged versions available on postcards with bigger pictures, coffee cups, and trading cards, I find three different traditions, equally represented on postcards issued in Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, explaining the attractive and/or spooky moss which was frequently used for bedding or insulation, and was reputedly the preferred stuffing for the earliest bayou voodoo dolls.

One set of postcards is part of a general “star-crossed lover” tradition which has rots extending to Greek Myth and can be found in every part of the planet. In this version, rather than two lovers divided by war or feud, we have an engaged couple “a thousand years ago” (sometimes named Hasse and Laughing Eyes) whose wedding never happens because Hasse is killed in an attack by a rival group. In one telling, they are killed together while in others, Laughing Eyes dies of sorrow. In either case, the lovers are buried together, Spanish moss appearing on the oak which grows from the grave, presumably the muscular hero being the tree hung with the hair of his beloved, which goes gray with the passing of years.

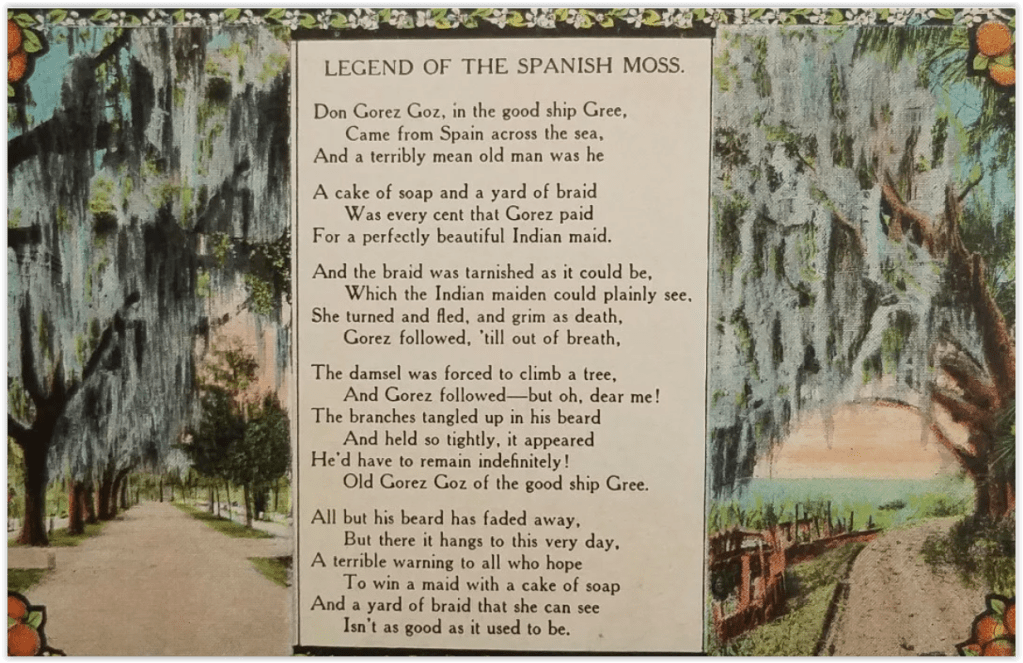

This is pretty standard stuff, so let us turn to the two traditions of Gorez Goz, a name I refuse to believe in. The tale of this Spanish sea captain, whether he is an outright villain or unfortunate schlub, comes from two poems, one credited to P.M.L., and the other by T.S.Y. (The latter poem is sometimes known as “The Meanest Man Who Ever Lived”, though I have not seen this title on a postcard.) The chief difference between the two appears to be the motivation of the fleeing Indian princess. In the version seen at the top, she is afraid of the bearded captain and sets off into the swamps, whereas in the other version (here shown in abbreviated form), she is offended by the fact that the braid of thread Gorez offers for her is tarnished, and runs off because her pride is injured. In both, the captain’s beard defeats him, catches in the trees, and becomes Spanish moss.

I have hunted without success for where in the world the name of the captain comes from (in the second poem, his ship is the good ship Glee, easy to rhyme but just as unlikely as its captain’s moniker.) There IS an account online which traces the story to the 1764 wedding of a French sea captain with an Indian princess who died not long after the wedding and became the subject of a religious argument, the captain wanting his wife buried while the lady’s family demanded she be exposed on a platform according to their tradition. The captain compromised by burying his wife but exposing locks of her hair in trees. THAT then became Spanish moss. The captain and his ship and his bride are named in this version, but as I found this in only one source, which goes on to note that the princess was the daughter of the Choctaw spirit Father of a Thousand Leaves, I will set it aside. Anyway, it’s not on a postcard.

The only reliable chat about the whole legend tells how, to tease each other, Spanish explorers in the region referred to Spanish moss as “French hair” while the French explorers called it “Spanish beard”. I have failed so far to trace either of the poets known by their initials, so unless someone out their can prove to me that the L in P.M.L. stands for Laughingeyes, I am going to take it for granted that the name came first, and the ancient legends came later, about the same time postcards needed to be sold to romantic tourists. (This WOULD make it even younger than the joke I’ve decided not to make, about something like this being afoot in most legends.)