Okay, M. Bergeret, you’ve got me. Explain the joke.

Not long ago, I added to my inventory a collection described as an assortment of postcards roughly 120 years old, based primarily on French silent movies: mainly comedies. Among these, among scenes from a Dutch documentary of the 1950s and a German drinking song postcard or two, were numerous works from A. Bergeret et Cie.

Albert Bergeret set up as a postcard publisher in 1898, and by the turn of the century was printing seventy to a hundred million postcards a year. (Have I mentioned what a HUGE fad postcards became?) These were almost all photographed subjects: cute kids, weird fantasies, and one series I’d like to see more of, in which pinup models interacted with punctuation marks. Some of the cards I have do seem to be scenes from morion pictures or stage productions of the early twentieth century. (The Bergeret imprint lasted only until 1905, when he merged with another company and took a different name for the combined company.)

We have discussed hereintofore the early postcard trend toward series of postcards, and have even mentioned specialized series in which a long poem or popular song would be divided by verses into several postcards. So I was not sure, when I saw these three cards from a “Sur la Mur” series, whether I was dealing with a movie, a poem, or a song. I’m still not.

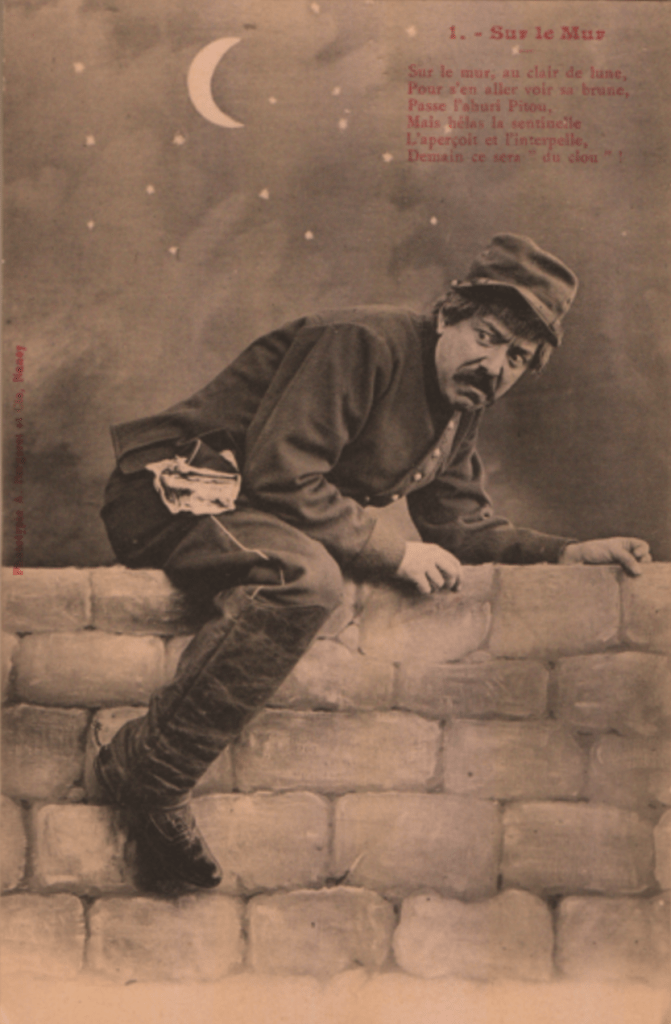

Part of the problem is the relationship between me and the Interwebs. YOU try looking up “Sur la Mur” online. When the Interwebs wasn’t trying to sell me postcards “On the Sea” (Sur la MER) they were showing me postcards about love (Sur l”AMOUR.) OR they were showing me people who decorate their apartments with postcards on the wall, which is closer to my literal search but got me no nearer to the postcards in hand. Here’s #1 in the series, by the way.

Here we have a nice little poem, which I will NOT try to translate into verse, about Pitou, a popular stage and movie character, a hapless and put-upon soldier. Here we are told that on the wall, by the light of the moon, he sneaks out of camp to see his brunette. But the guard spots him and hollers and tomorrow, we are told, will be all cabbage. Somebody else will have to cover the complex subject of cabbage in French idiom, but this is a sympathetic and entertaining little vignette. Let us consider postcard #2.

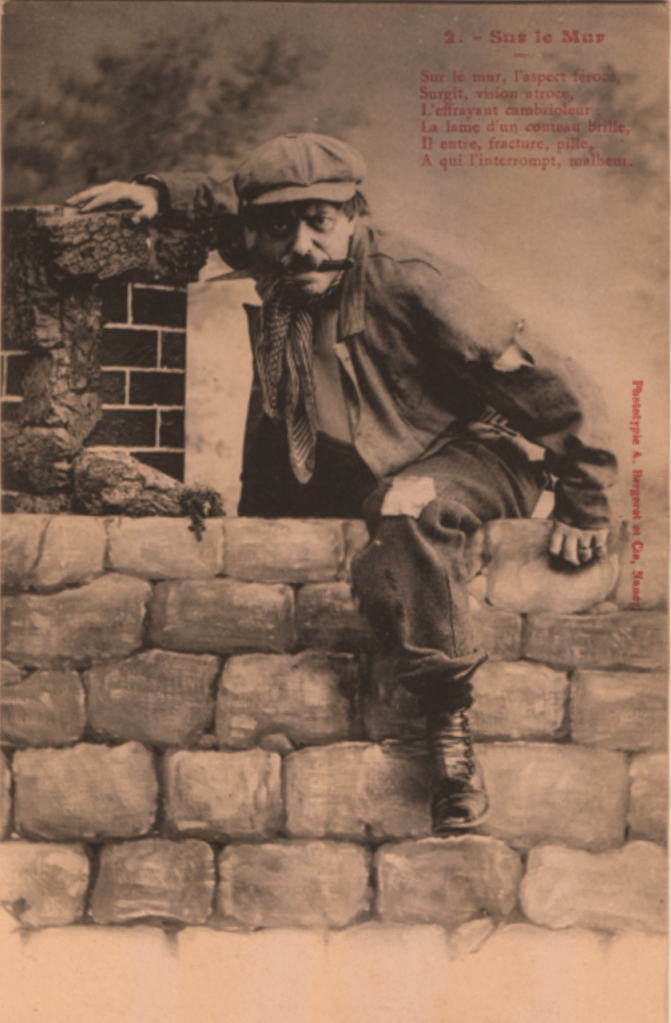

On the wall, with ferocious face, rises a horrifying vision: the fearsome burglar. His blade flashes in the moonlight as he breaks and enters to pillage. Bad luck to anyone who interrupts him! I admit that Pitou was not so cute as HIS poem suggests, but we have definitely changed key. What kind of creature will face us in postcard #3?

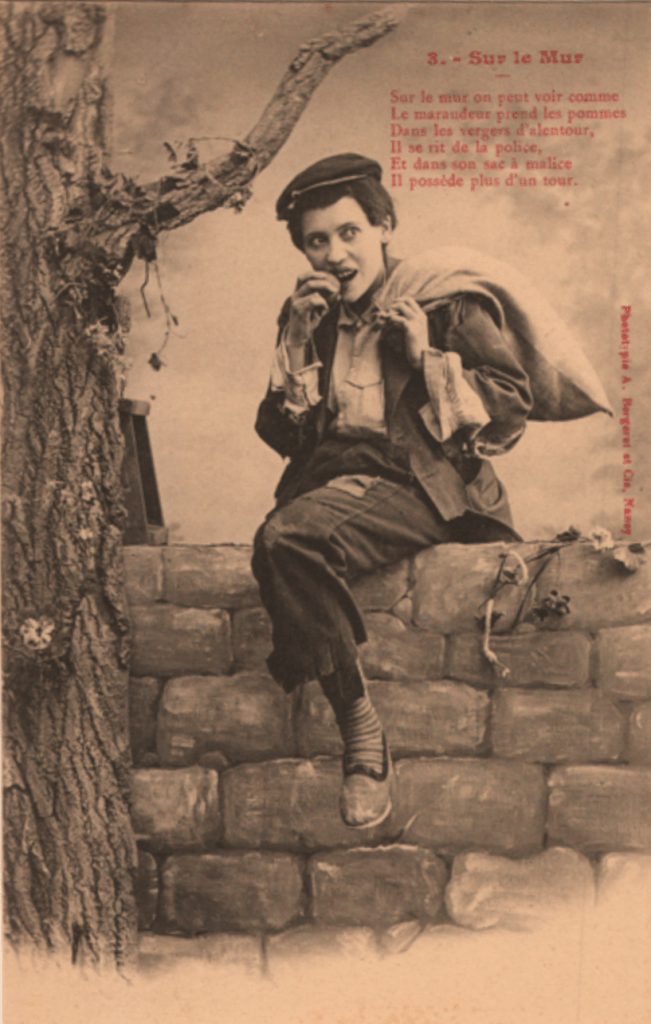

On the wall, a marauder swipes apples from the neighborhood orchards. He laughs at police, and in his heart is a malice that tells him to do this again and again. Do you see the natural progression of crimes here? Me neither. If we’d started with the boy thief, turned him into a luckless soldier, and THEN had him turn to burglary, that would have produced a typical Victorian song about the inevitable decline and fall of naughty children. That isn’t what M. Bergeret had in mind. These pictures are not pf the same person. Heckfire: it’s not even the same wall.

And, moving on to the 64,000 franc question: is this it? Or were there further cards, at least a fourth one to pull the story together? Maybe the Bergeret employees simply found they had unrelated photographs of different characters and walls, and decided to write a few poems to make them marketable. Tell me whatever you can about the subject. I’ve run into a…ah, sit down. You must have seen that coming.