Last time, we observed the existence of Thanksgiving postcards, and noted that most people do not send such greetings nowadays, partly because there’s so much going on at the end of the year (one reason the Farmer’s Almanac keeps promoting a “rational” relocation of Thanksgiving to the first Monday in October) and partly because the price has gone up. You CAN buy a Thanksgiving greeting card, but the cost plus postage will run you around seven or eight dollars now, whereas in 1908 the price of card and postage would have been about two cents. MUCH easier to just email someone a turkey cartoon and get back to your regular holiday shopping. (And why DON’T stores sell Black Friday cards?)

One or two people felt I was rushing the season. Well, let’s REALLY look ahead, then, and consider the existence of cards intended for people to send to wish each other a Happy Leap Year.

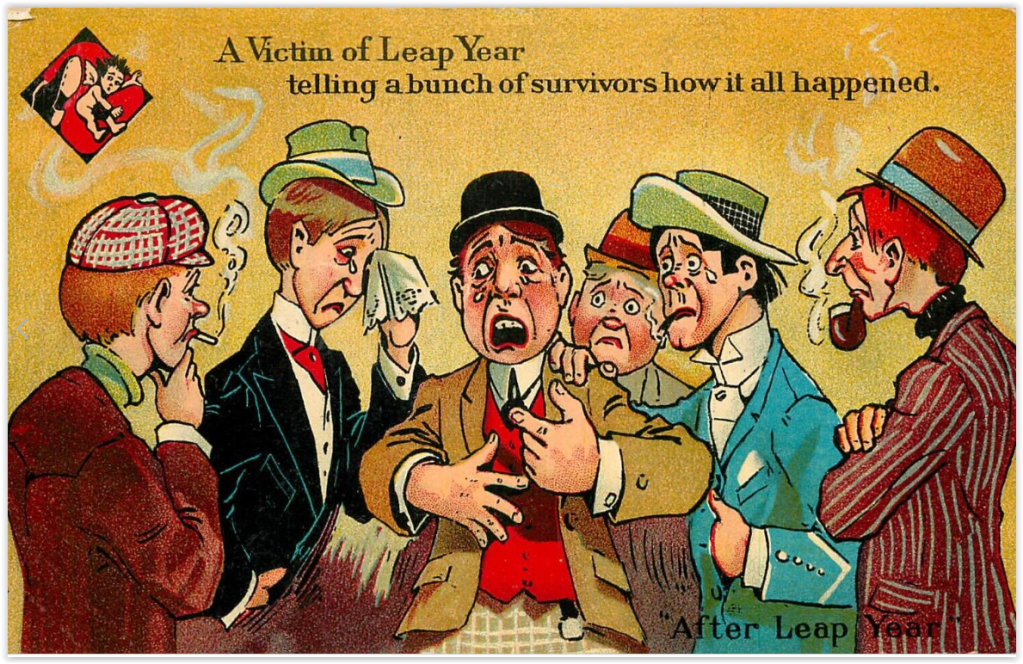

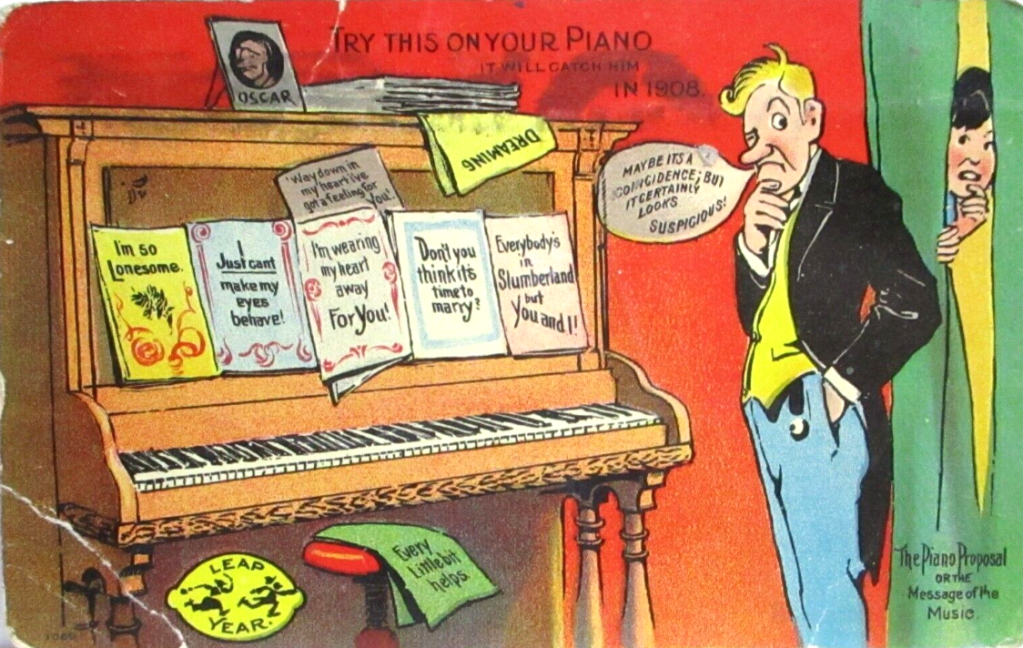

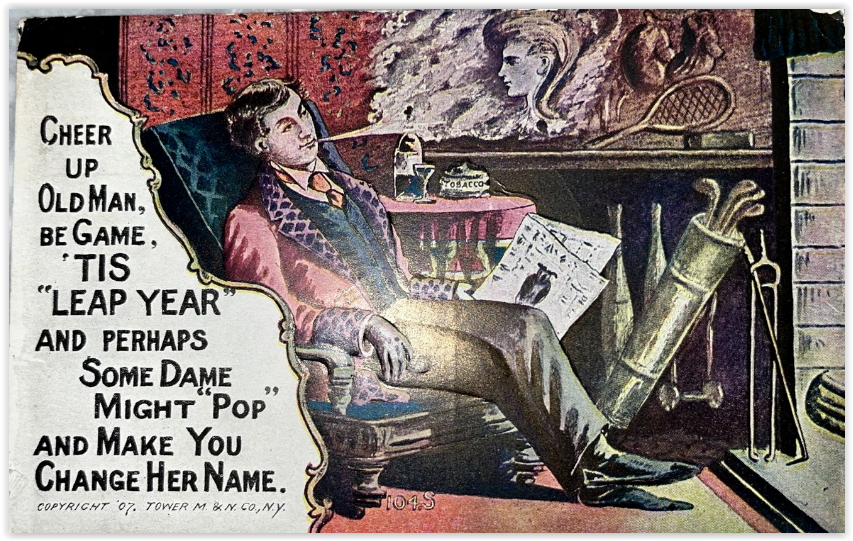

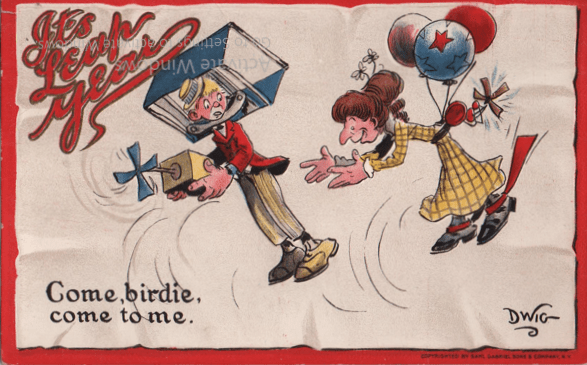

The Leap Year postcard is a fairly limited proposition (so to speak). It was wildly popular in 1908, and then again, though apparently not quite so voluminously, in 1912. A few companies bothered with them after that, but it isn’t all that profitable to produce a line of cards which are useful only every fourth year. And the raucously funny tradition started to slip away.

See, for a couple of generations, there was a jovial tradition that during Leap Year, it was socially acceptable for a woman to propose marriage to a bachelor. The tradition began when…well, the fact is that nobody really knows. This doesn’t mean there are not explanations and historical tales, as collected by Stanley Buttinski in the book we mentioned in one of last week’s columns.

One tale claims that the lady who would one day be known as St. Brigid had a long discussion with the man who would be named St. Patrick (getting his own holiday and postcards one day), demanding, in the way Irish women had, some equal rights. She wanted Irish women to have a right to ask Irish men to marry them, as Irish men are considered to be really slow about getting around to such things.

St. Patrick, who had traveled far in Ireland and met a lot of Irish women, felt they were pretty powerful already, but finally allowed as how this would be permissible: on February 29. One day out of every four was all he felt Irish men could afford to lose the advantage. Some subsequent authority decreed that this would be true ONLY in Ireland.

This story does not apparently appear in any of the earliest lives of either of these saints, and the tradition DOES exist in other countries as well. Scotland lays claim to it due to an old tradition that Queen Margaret decreed in 1288 (a Leap Year) that any man who turned down a woman’s proposal would be fined by the government. Your non-romantic historians point out that Queen Margaret was only five years old in 1288 (she died three years later, without having proposed to many possible consorts). In Finland, however there is a tradition that any man who turns down a woman’s proposal in Leap Year must buy her the material to make a new dress. Other countries insist on reparations in the form of cash or twelve pairs of new gloves (one for each month of Leap Year, you see.)

Other stories trace the tradition of “Bachelor’s Day” or “Ladies’ Privilege” to some seventeenth century comedy, which is deemed responsible as well for an idea that said proposal is only valid if the lady is wearing breeches, or a scarlet petticoat.

But the most conservative historians still claim the whole thing sprang up as a joke some time after the Civil war, which puts it in pretty much the right era to be snatched up by postcard manufacturers. These are the same sort of people who claim there never was a Stanley Buttinski, as noted last week.

I ran into a number of bewildered bloggers who claim that it is only with the advent of social media that women feel comfortable proposing to men (honest? YOU guys invented it?) and others who confuse the whole thing with Sadie Hawkins Day, when, on college campuses around the United States, women could ask men to go to a dance. This day was NOT February 29, as a few of these bloggers state, but an unspecified date in late October or mid-November, which brings us back around to THIS month. (It derives from Al Capp’s Li’l Abner, and like any good comic strip artist, Al Capp left the date vague, so he could slip it into the strip without interrupting whatever story he happened to be telling in fall. Shortly before his death, and the end of the comic strip, he stated that November 26 was the correct date. He was too late; for years before that Sade Hawkins Day had been settled on as November 13.)

What the POSTCARDS say about the tradition leans toward the “whole year” version of the story, rather than just February 29, and they ignore the question of who started the tradition. Getting in on it, as Minnie Pearl said in one of her jokes, was more important than any other considerations.