Among twentieth century artifacts which occasionally confuse those who inhabit the century of the Interwebs is the slate. These can still sometimes be turned up at garage sales, but besides being breakable (especially when real slate was used and not just heavy cardboard painted black) they were also often given to children to play with when their other uses faded away. (Some dairies gave them to customers to write their orders on for the milkman; coal companies would apparently do this as well: the reappearance of deliveries in the Covid age could bring them back, if texting weren’t so much easier.)

And, after all, they were the tool of children for many years. When Bill or Belle started school, they had to have their school slate: a piece of slate of 5 by seven inches or thereabouts, with a frame, on which they could practice penmanship and math. More renewable than a notebook (since what was on the slate could be erased and replaced), it was also a lot heavier. The question of convenience, as well as the fact that paper is a more easily renewed resource than sheets of slate, went into changing us over to other ways as time passed.

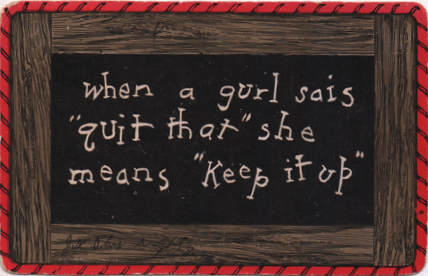

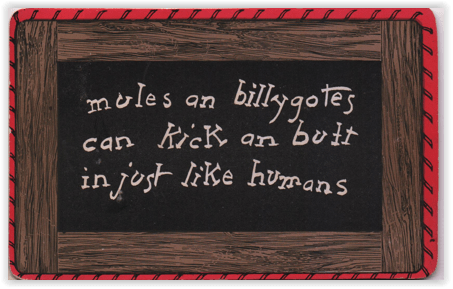

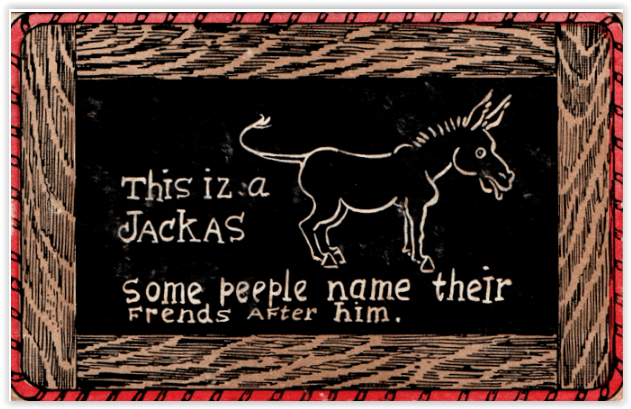

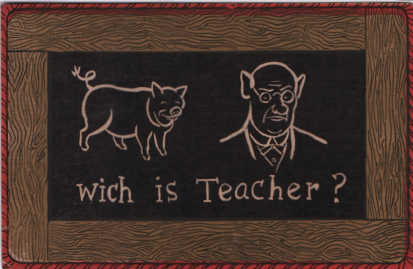

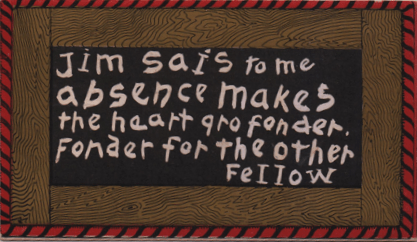

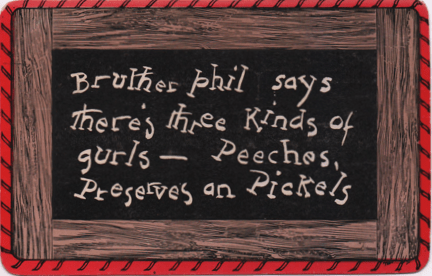

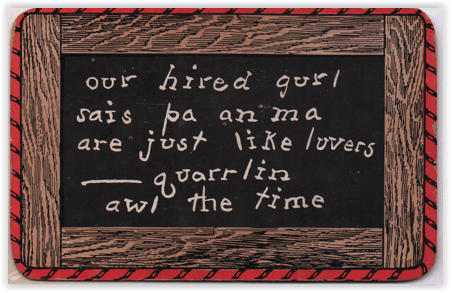

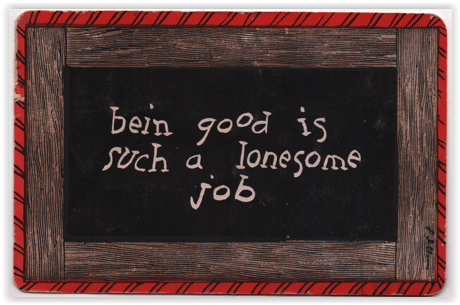

Which makes the postcards based on the technology a little obscure to people in these latter days. But between 1907 and 1911, or thereabouts, dozens of different wisecracks and witticisms appeared in this standard form: something written, generally with at least one misspelling, in a childlike hand, as if with chalk on a school slate with a (printed) “wooden” border within a small (printed) “fabric” outer lining.

It was all part of a phenomenon we’ve discussed before: a straight statement is funnier if delivered with an accent. Extending this idea to misspelling, we have tapped into a vein of American humor which was already old by the time of the Civil War and had not yet passed off by World War I, when Dere Mabel was a nationwide bestseller. (This is also why books like Dere Mabel or the works of, say, Josh Billings or Kin Hubbard are seldom seen now: our impatient age finds them too hard to read, even in the era of bad online spelling.)

Several companies appear to have made use of the basic plan: if you look closely, you’ll notice the wooden border is not uniform from card to card, nor the handwriting and spelling. Flipping the cards over shows the same inconsistency: it was simply a way for a cartoonist to take it easy: no need for an elaborate drawing: one halfway decent wisecrack (picture optional)_ was all you needed once the basic template was established.

The jokes MIGHT be schoolchild related, but they didn’t need to be.

But most gags were, no matter how they seemed to be a child’s work, written by and for grownups.

One other great humorous tradition was part of the mix as well. Some things just appear funnier if you claim someone else said them. YOU aren’t the wise guy; you’re just passing the story along.

I wanted very badly to find a cartoon family, executed by one artist to create a humorous cast of characters, but, alas, these cards also appear from assorted publishers.

So Jim and Phil and Sis and the hired help are not all part of one big dysfunctional family, but apparently represent various rural (the slate disappeared in the cities first; those little one room schoolhouses beloved of American folklore took longer to convert. Have I told you what my grandfather had to say about HIS one-room schoolhouse? Nother blog.)

By the way, though Ma is mentioned, and even drawn, on some of these cards, I have yet to find her getting credit for an observation. Maybe I haven’t found the right card yet, or maybe she was considered above making wisecracks. (Must pass along some observations on my grandmother, too, now I think of it.)

But there isn’t really time or space to cover ALL the possibilities of the slate postcard. And we haven’t even touched on, say, a number of postcards mailed using real slate, or sayings like “a slate of candidates”, but, after all, we can’t do everything on one column. So we will conclude with a note oft expressed on slate and other postcards, and save the rest for another column, when we can start with a fresh slate.