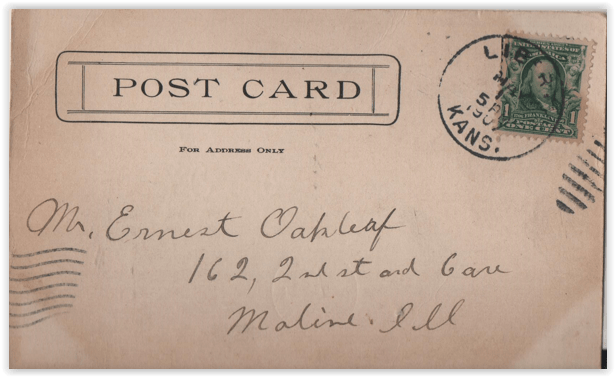

When we mail a letter, we do not have to write LETTER on the envelope. Our packages may have notes on them about Media Mail or International Ground, but we don’t need to label them PACKAGE. Still, postcards go right on explaining to people what they are, with the word POSTCARD (or sometimes the words POST CARD. But that’s a whole nother blog.)

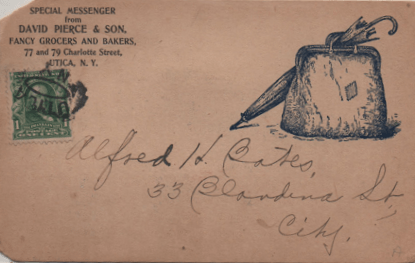

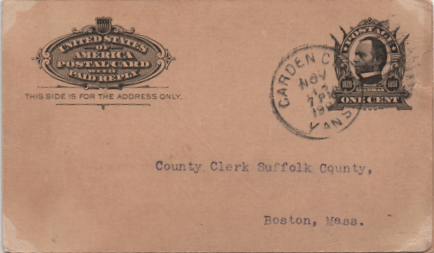

It was not always thus, as can be seen from this advertising postcard from 1894 or thereabouts. A card could be plunked in the mail and left to the wise decisions of the U.S. Post Office.

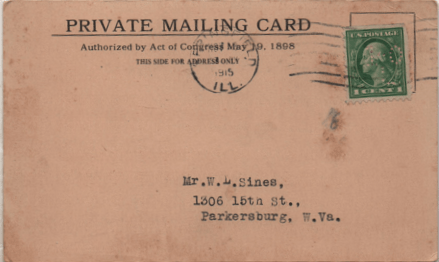

This was way too simple for the government, however, and in 1895, a law was past allowing people to send postal cards OR private mailing cards. (This one, from 1915, is from long after most of us stopped using Private Mailing Cards, but some companies like to do things the same way year after year without a lot of contradictions or concerns.)

A Postal Card was an official U.S. Post office publication, and cost a penny when purchased at your local post office. This covered the price of the card AND postage, whereas a Private Mailing Card (or Post Card, as it came to be known, in the belief that someone at the post office would be able to tell the Post cards from the Postal cards) cost TWO cents. This is the kind of strategic thinking which has made Congress the guiding light of American Wisdom.

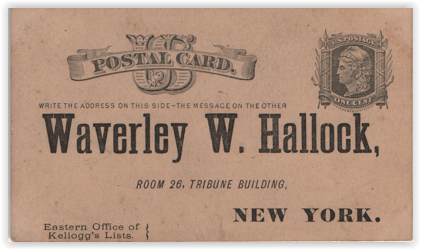

Postal Cards also came with the postage (which you’d already paid for) printed on it, which led to numerous designs honoring this or that president. (This was at a time when most of our postage stamps had either Benjamin Franklin or George Washington on them, so it allowed for variety.)

There were also special Postal Cards which could be purchased with prepaid reply cards, if you wanted to make sure your customers replied.

OBVIOUSLY, to help the Post Office know what they were dealing with, U.S. Government Postal cards SAID they were Postal Cards, and Post Cards had to follow suit. Since the postcard craze spread around the world in no time at all, and other governments were as picayunish as our own, some companies made sure their cards were labeled in more than one language.

Ambitious companies going for wide international sales went further. I think my record so far is one card which had the word in twenty-four different languages, an important thing in the era before World War I when a card might cross several different language areas without ever leaving, say, the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

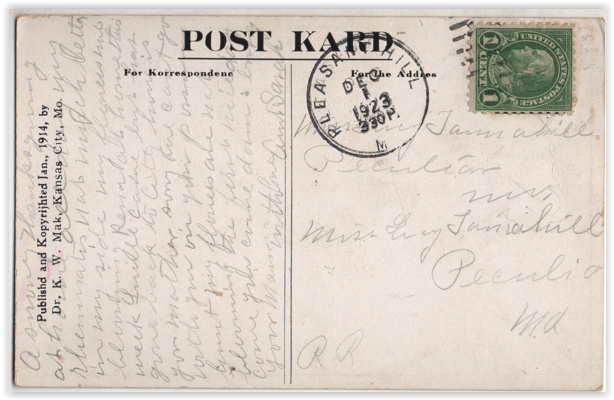

Other publishers went their own way. Remember Dr. Mak, the multi-talented alphabet reformer who made his own postcards? Well, he labeled his, but in accordance with his spelling regulations.

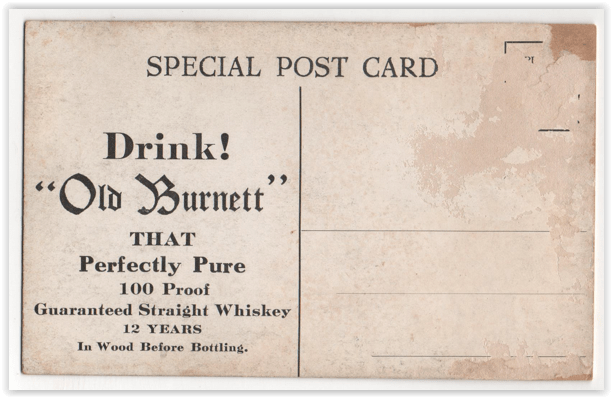

I don’t know if “Special Post Card” was an official U.S. Post office category, or this whiskey company came up with the idea on its own.

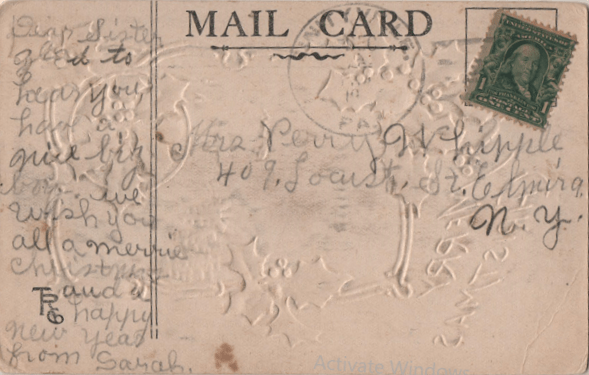

And, of course, there’s always somebody who doesn’t QUITE read the whole memo. But this is why our postcards put their names on the front (You may remember that rule, too: according to the U.S. Post office, the front of a postcard is the side with the address on it. Well, it’s the side THEY have to deal with.)