If I ever get around to writing that series on “Is That Still Funny?”, we will look into what different generations regarded as taboo. As we have moved, in the last thirty years from “Nothing inoffensive is funny” to “Nothing offensive is funny”, this will be a mere side issue, but one which will use up a lot of space (which is the main goal of every blog writer.)

We have, hereintofore, considered the many representations of round people on postcards, without mentioning a side issue. It isn’t a universal feature, by any means, but in general once a woman passed a certain age, she tended to go round. But only if she was married. Unmarried women, as they got older, seem to have gotten taller and skinnier.

To some degree, it was a matter of fashion and perception. In another one of my digs into the archaeology of humor, I ran across a college newspaper of the 1880s which warned young men NOT to look at each other’s new mustaches and mutter “Too thin, too thin”, lest some of the female students think they were being insulted. That hourglass figure we still cite today required a great deal of sand at both ends of the timepiece.

(I have also run into a number of experts in fashion and figure who say we have exaggerated, as years have passed, how much the Victorians demanded plumpness. One scholar, after studying pornographic photographs of the 1880s and comparing them to similar photographs of the 1980s stated straight out that the nude models of the earlier century were just about 8 pounds heavier than those of the later date. Thus proving that it IS possible to find interesting jobs in statistical research.)

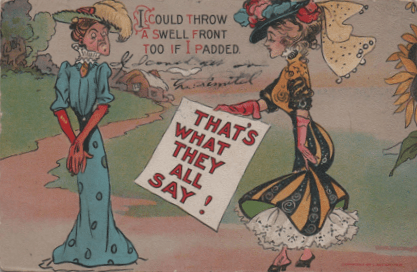

In any case, the stereotype of the tall, skinny old maid was firmly established in the vinegar Valentines and other jocular greetings during the first golden age of the postcard. (This example, mailed in 1908, puts the blame on her disposition rather than on her figure.

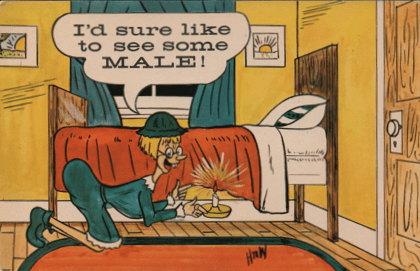

Another joke of the period, which I have not found on a postcard so far, is that some padding of the figure might be necessary for Cupid’s arrow to strike a young lady; otherwise there was a risk of “narrow misses.”

Which many a narrow miss sniffs about on mischievous postcards.

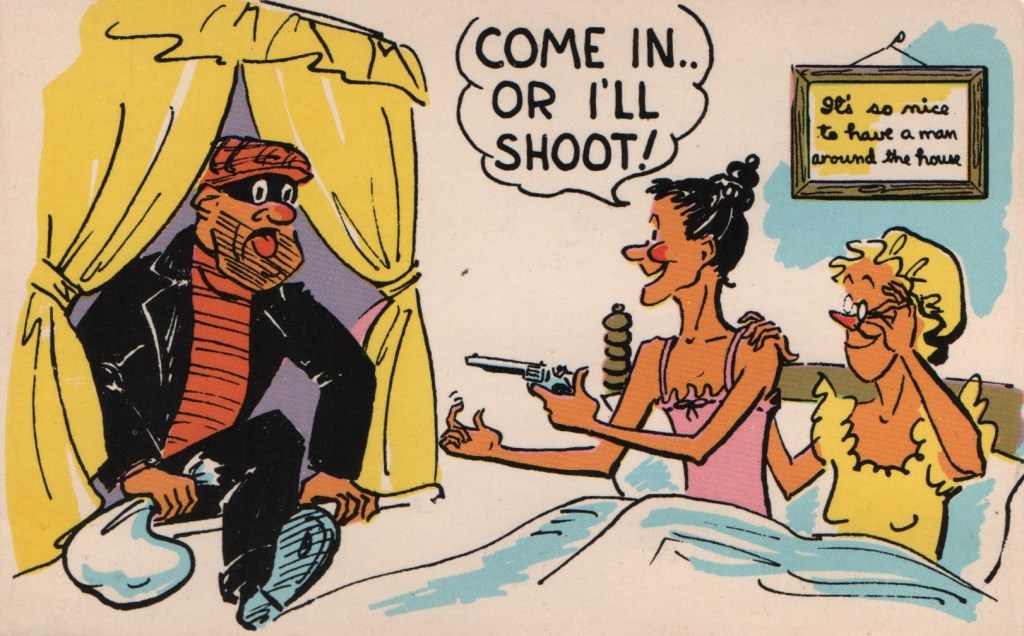

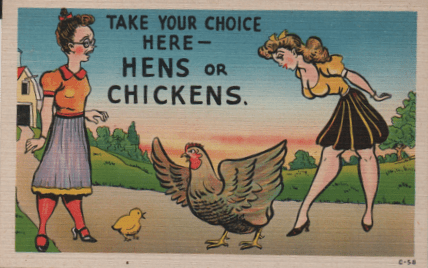

What is interesting, given our association of plumpness being a Victorian erotic requirement is that the tall, thin caricature went on representing an old maid long after the era had passed. Part of this can be attributed to comic actors like Charlotte Greenwood or Martha Raye, who emphasized their height and gawkiness to carve out careers as man-hungry unmarried women for decades. A more voluptuous contrast was often provided to make the joke more obvious. (Subtlety was not considered Box Office; neither was a movie completely devoid of cleavage.)

There is this, for example, where the goal was to present women both prudish and clueless, but the one on the right had to have SOME curves in the right place, or we might have missed the joke.

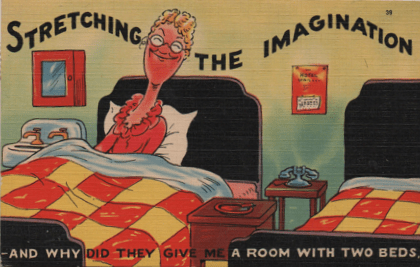

The institution of the unmarried schoolteacher is something someone else can write about, but they and librarians were fair games for this sort of gag for two generations. (It has to do with two World Wars in quick succession, a belief that no woman would take a job if she could find a husband, and the fact that any authority figure is fair game for any kind of joke, but you can cover that in YOUR blog.)

And, anyway, the ladies involved were at least up to our modern standard of people who don’t let advancing years and body shape dampen their dreams. So you see, if looked at from the right angle, this offensive stereotype is actually not offensive at all. (Yeah, I know; I’ll try that one again in another ten years or so.)