Looking back now on the six surviving silent movie versions of A Christmas Carol (there are at least three lost versions), while remembering that two of the six are fragments AND that we are seeing them on a small screen, what did we see?

SETTINGS: The 1913 version does the most with exterior scenes. Scrooge’s apartment is almost always teeny, but kudos to 1910’s producers. Someone read the book, and the seldom-seen Dutch tiles appear around the fireplace. All versions make an attempt to be Victorian in furniture and fashion, with the possible exception of 1901, which is the closest to BEING Victorian. The cemetery is almost always bland, relying on Scrooge to create any interest.

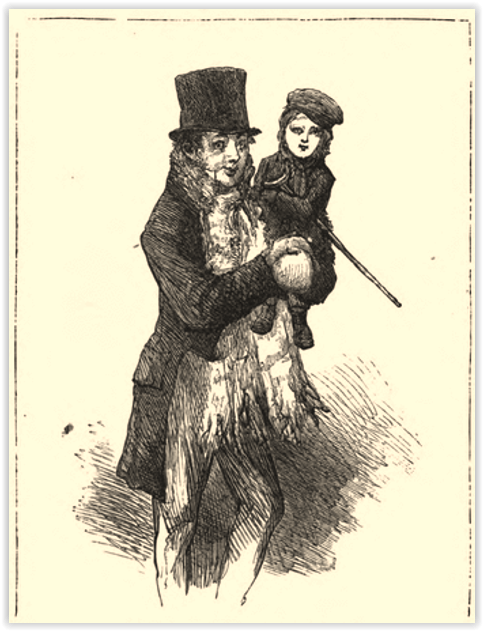

SCROOGE HIMSELF: Ebenezer is generally of advanced years: he is youngest in 1901 and 1913 (entertaining, as THAT version was also released as “Old Scrooge”.) His personality is dictated by the text, and we don’t get much extra, beyond what each actor chooses to add. The 1901 Ebenezer is jumpy for no apparent reason: perhaps this was the actor’s standard React Mode.

CRATCHIT/CRACHIT: Bob is generally older than he appears nowadays; he has a receding hairline in all but 1922 (the youngest of Bobs) and 1914, where he is given Harpo Marx’s hair. He is almost always to be seen trying to rub his hands together to keep warm. The filmmakers give him, less to do, for some reason, in the 1920s.

FRED AND THE CHARITY SOLICITORS: These episodes play a part in most versions (Scrooge is chasing somebody out when we open in 1901). They are not easy to manage without spoken dialogue and get more attention as title cards become customary. Fred usually gets more room to play; it is with a shock that we see him slap his grumpy old relative on the back. Scrooge is in excellent malevolent form in these scenes in the 1923 version.

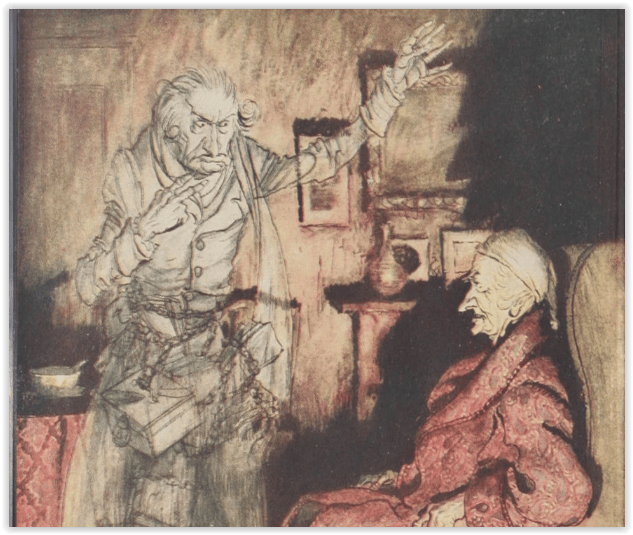

JACOB MARLEY: Two versions are brazen enough to leave out Jacob’s face on the front door, but two are brave enough, in a silent movie, to include the doom-ringing of the bells. Most Marleys are fairly unfrightening: he becomes more realistically human as we move through the twentieth century, and more attention is paid to his chinstrap, pigtail, and chains. (In 1922, he is chained to rolled documents, appropriately financial but surely not all that heavy.) He gets more dialogue as years go by, too, but the filmmakers, then as now, cannot resist rearranging and rewriting his dialogue. His 1914 incarnation looks the most like someone who is suffering in Hell, rather than a temporary escapee.

CHRISTMAS PAST: This ghost is very hard to render as described in the text, and appears in as wild a variety of forms as in the talking versions. The lonely boy Scrooge at school seems to have struck a chord: we see this in four of the films, though he is rescued by his sister in only three (whether she is older or younger than Ebenezer is as undecided among these versions as ever). Scrooge’s fiancée is in four versions, and the Fezziwig party is attempted twice, most elaborately in 1914 (note the fiddler sitting up on the wrapped bales.) In 1922, however, we see only young Ebenezer getting grumpier at his desk in the office.

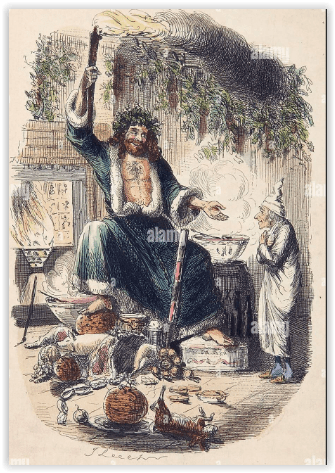

CHRISTMAS PRESENT: This Ghost USUALLY limits itself to the Cratchit home and Fred’s Party, though in 1923, he drops by only long enough to say he can’t stay. The Significant Children appear in the 1910 version: one out of six is probably a better percentage than they got in the talkies. His costume adds more and more bits of Father Christmas as time goes by.

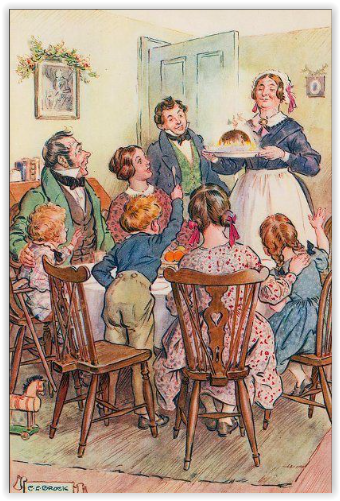

CRATCHIT DINNER AND TINY TIM: This is almost always present (in 1923 the whole family is omitted, and in 1922, they are not eating) just to show Scrooge a happy family, reproving him for his solitary and selfish nature. Tiny Tim has very little to do, though he does Martha’s hide and seek in 1914, and in 1901 actually gets to raise his toast. He is seldom named in the title cards (they assumed you’d READ the book, and KNEW). In 1922 and 1923 he is omitted, though he MIGHT be the small child playing with the abacus in 1922. Only in 1913 does Scrooge show much of an interest in him.

FRED’S PARTY: The party is smaller than similar scenes in the talkies; its major expression comes in 1924 (where it is NOT a scene presented by the Ghost od Christmas Present.) This is the first version in which Scrooge almost chickens out and goes away, a theme treated with gusto in later versions.

CHRISTMAS YET TO COME: This Ghost has the least to do, and shows Scrooge little beyond his tombstone. Most of the other scenes in the text are hard to do without spoken dialogue, but in compensation an attempt could have been made to make the Ghost scarier, at least. No one plays with Dickens’s hint about a resemblance to the Grim Reaper. (This COULD have been considered too horrific to get past local censors, of course.)

THE MORNING AFTER: All versions (especially those where a spectral Scrooge rises from his unconscious body to accompany the Spirits) make it possible that the whole thing was a dream. Scrooge always points to parts of the room as evidence that it all happened, though, and sometimes hugs his bedcurtains (for no particular reason except to those who read the book, for the stealing of them never occurs.) And Scrooge is definitely as giddy as a drunken man, giving the lead room to emote.

THE CHEAT ENDING: I spoke in the original series about the irresistible urge to have Scrooge take the turkey to the Cratchit home himself, so he can meet the kids and have a big, happy finale. In 1913, Scrooge IMAGINES this, but 1910 preceded this with a genuine Cheat Ending and our very first group hug at the ending. (Anticipating future versions, Fred and his fiancée have slipped in behind Ebenezer with the basket of goodies, and can join the holly-jollity.)

SCROOGE AND BOB ON BOXING DAY: Most filmmakers loved Scrooge’s nearly disastrous joke on Bob at the office (Bob comes close to braining his employer, as in the text, several times.) But in 1924, perhaps because it is Fred who is the secondary hero, we just see Bob looking very uncomfortable in Scrooge’s apartment, getting a glass of punch.

ADDED BUSINESS: Even Charles Dickens admitted to the occasional impulse to supplement the text (and he did, in his readings.) 1910 is the first to give us an unmarried Fred, so Scrooge can save HIS future by making him a partner. It is also the first to give Scrooge a death scene, and tries to bring the story full circle by having him wakened in the morning by ragamuffins singing “A Christmas Carol”, a nice touch not really possible in a sound movie. 1913 has a whole opening section which could have made a short film called “Ebenezer Vs. The Children”, as well as informing us that Ebenezer “rejected” his sister in later life, which is not part of Dickens’s story. In 1914, the only version to include Scrooge’s evening meal at the tavern, we have him lashing out at the waiter as well as his fellow diners; we also get his violence against the apple woman and that bizarre inclusion of his name on the turkey for the Cratchits. 1922 gives us the firm of “Marley & Scrooge”, and the reformed Ebenezer’s obsession with creating HAPPINESS. 1923 adds Topper’s proposal, and Scrooge hosting Bob to punch at home.

SHOULD YOU WATCH? Are any of these of more than historic or fanatic interest? That’s in the eye of the beholder. Maybe you just want a slightly different Ebenezer, come Christmas, and can take a chance on something silent (some versions do add a soundtrack: everything from cylinder recordings of Christmas songs to one ambitious soul who linked up one of Lionel Barrymore’s radio tellings of the story. (There were several, and the differences…but that’s a whole nother blog.) Would I recommend one? The Ghosts are at their best in 1910 and 1914. Bob is excellent in 1914, and Scrooge in 1923, though Sir Seymour in 1913 runs an entertaining second. On the other hand, the print from 1923 is hard on the eyes, and…oh, watch them all in one evening. That takes less time than most modern versions, and you get six times as many Scrooges for your time.

Next week: Back to Fiction.